HP Memories

Don Anderson, the head of HP's purchasing activity that I had worked with earlier called me over one day and said that he wanted me to come and work in purchasing. I thanked him for the confidence, but told him that I didn't feel that was the right direction for me. Sometime later Bob Sundberg, who was the head of all materials activities, including Don's purchasing department asked me to stop in. When I did, he reaffirmed the offer and hoped that I would consider the possibility more carefully. Again I thanked him, but said I just couldn't take the offer. Shortly after that Ed Porter, VP of manufacturing, who was Sundberg's boss, called me into his office and asked if I wouldn't take the assignment in purchasing. I told Ed no, I really, really didn't want to do it.

The NY Giants had moved to San Francisco and one day a number of my fellow workers decided it was time that we saw a real major league game now that we could. I believe it was a Wednesday that the Giants had a day game. I'd never before cut out of work on a week day, but thought this one afternoon can't hurt. I've already worked a lot of extra time and I'll certainly do more in the future to make up for the lost afternoon. So we all went. The next day everyone said that Packard had been looking for me all afternoon. I went over and reported in to Margaret Paull, Packard's tough-as-nails secretary. She said hang on a minute and in a short time sent me in. The company still had only two enclosed offices, one for Dave and one for Bill, but now there were a few smaller ones, open at the top, for Executive Vice President level managers like Porter, Cavier and Eldred.

Dave chatted in a friendly way for a short while. Baseball never came up. Then he said, "We'd really like you to take the job in purchasing." I was taken aback. As my mind raced through possible responses, I concluded that it was time to give the real reason for declining so consistently. So I told him that I was concerned about the way the department was currently functioning and that it would be very difficult to put it right without making significant changes which could hurt a lot of people. He listened carefully and then said, "That's why we want you there." I said, "OK then, I'll do it."

Just at the time I was coming over to purchasing Don Anderson announced that he was moving and would be leaving his job and that I was to take his place as head of purchasing reporting to Bob Sundberg. So I began to dig in. We made a number of simple process changes that seemed to work well.

Some changes were not popular. I asked the purchasing agents to stop going out to lunch, or dinner with vendors. Instead, if they needed to work with vendors through lunch, we had the department pay for the two of them to eat in the HP Cafeteria. Instead of dinners out we periodically invited our major suppliers into HP for a nicely catered dinner on site with table cloths and wine. This served to recognize that gratuities like long lunches were no longer to be tolerated. The evening dinners started with a plant tour. At the banquet, we had senior HP managers give some HP orientation and at the same time thank them for their efforts on behalf of HP. Bob Sundberg and Ed Porter coached me on the appropriate wine to serve for these occasions, because I had no clue.

We also let the vendors know that we no longer wanted Christmas gifts and if any still slipped through we gifted them to the Veteran's hospital. As a result of these changes we no longer had missing afternoons and we became less socially beholden to our vendors. These changes set a more realistic business tone for the purchasing department, however the real problems had yet to be addressed.

|

| A tour before dinner with a portion of 250 suppliers who attended a "vendors' night" at the Stanford plant are seen during tour with Hank Taylor (right). Courtesy of the Hewlett Packard Company |

The Personnel Department had training courses for new managers. They asked me to teach one of these and I was first teamed up with Gene Doucette, who had been a school teacher and had broad experience in HP. Our group met several evenings a week, after work. About 15 people were in the group. We focused on the HP styles of leadership and the instruction seemed to be well received. I had the opportunity to teach a number of these and other courses over several years.

In that first class, one of the illustrative stories I used came from the Pacific during WWII. It was told of a destroyer captain who described some of the fierce sea battles he had been in. Several times he had the chance to pursue an enemy vessel, but could not keep up with them. He repeatedly barked the order down the communication tube to the engine room to give us more speed, but got no results, so they could not keep up with the target. When things calmed he went down into the engine room and told the men there all he needed was an extra 5 knots and our ship could hit more targets and be a big help to the whole fleet. The guys in the boiler room replied that they couldn't go faster because their boilers were scaled up.

The captain came back to the bridge discouraged. He pondered boiler scale and the somewhat sour reception he got in the boiler room. As he thought more about the engine room he realized that in all their battles these men were blind to all the surface action. More than that, in the depths of the ship they could feel and hear the pitching of the ship and the blasts of the guns, the torpedoes and the depth charges exploding, all without knowing if the next moment was their last. Except for being a blind target they had little idea how they fit into the efforts of the team. The captain's thoughts triggered an idea.

The ship had a fellow on board who had experience as a radio broadcaster and the captain ordered some work to be done on the public address system, especially in the boiler room. When the next battle started he put his radio man on the PA system. This broadcaster gave a vivid description of all the action as seen from the deck. Enemy planes were shot down; their large guns hit some targets. Every detail was broadcast. One of the enemy ships started to retreat and the destroyer captain started pursuit. All these details hit the boiler room and to the Captains amazement he had 7 extra knots. The pursuit was successful and the enemy ship was sunk. The captain went down to the boiler room and thanked the men and said we could have never done it without your great work. Just as the captain was leaving he turned and asked what happened to the boiler scale? The crew chief smiled and said we solved that problem days ago.

This was a great lesson on the value of keeping the whole team informed. I had Bob Sundberg who had been a radio announcer record the story with a little extra drama and we used that tape with numerous management training groups.

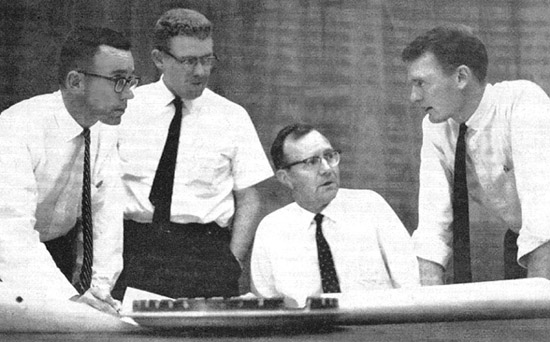

Sometime before my move to purchasing, Bud Eldon had taken over the Systems Group and had made some good process changes for the company. He stopped by purchasing one day and told me that the Material Engineering group in HP labs was ready to be transferred, or abandoned and a suitable home had not yet been identified. They were a talented group and purchasing used them extensively to determine if the products from manufacturer A were electrically and mechanically interchangeable with products from B. In fact once a product had been put into production they were the only group that could certify that a competitive manufacturer's product could be substituted for an original part, or certify that the next generation of a manufacturer's product was compatible with his old product and that our instruments would still work if we changed.

I told Bud about my organizational concerns in purchasing which were not yet resolved. We agreed that it would make a lot of sense to move the materials engineers into purchasing. Larry Johnson headed that Materials Engineering group. He was a workaholic wizard with electrical components. I liked him. The proposal was made and the transfer of about a dozen engineers to our purchasing group was made.

More Information Click Here to read a February 1964, PURCHASING Magazine article |

| L to R: Bud Eldon, Bruce Wholey, Ralph Lee and Hank Taylor talking about the plan to move Materials Engineers to the Purchasing Department. Click here for the article from Purchasing Magazine. |

This transfer put the 15 or so purchasing agents in an awkward position. They were the ones who gave the purchase order requests to typists and talked to vendors over their formerly long lunches. Order quantities were determined by inventory control under Dick Were and the items to be built into products were determined by the development engineers. These could only be substituted by the materials engineers who verified electrical and mechanical congruence. The purchasing agents' contribution was near zero.

This led to the dismissal, or reassignment of the purchasing agents. Just one stayed on to buy the non-standard items that had to be searched for and the purchase negotiated. Some of the departing agents transferred within the company to other jobs and some left the company. When all the dust settled 22 people had left the Purchasing Department and the full purchasing cycle for production materials was given to the Inventory Control Group under Dick Were who was already doing 90% of the job.

I hated firing people. On the days that I knew that this was going to happen I was nauseous and tense. Sometimes a reasonable and constructive discussion could take place, but sometimes it was a contentious, difficult exchange.

One of the purchasing agents that I dismissed was a great fellow, with many friends in HP. He often went hunting, fishing and to the Ranch with Dave and Bill and other senior leaders of the company. He very much enjoyed the social elements of a purchasing agent's role; the lunches and dinners with vendors and the review of their new products and the contacts with other HP people. Where he really struggled was being tied to a desk and spending significant amounts of time doing analysis and processing paperwork.

In working with him on alternative career paths, I invited him to go to Stanford and take a Kuder Preference Test and a Strong Vocational Interest Test. No clear results came from this. I suggested that he look into the career characteristics of a forest or park ranger. This didn't click.

The allotted time for his job search came to an end and he left HP. I didn't see him again for 5 or 6 years and then one day ran into him at a title company in down town Los Altos. We visited for a while. He looked prosperous, better dressed than his typical HP attire and was very upbeat and happy. After he left the woman from the title company who was helping us expressed surprise that I knew him and said, "He is the nicest and most respected realtor in the entire Los Altos area."

I thought about this for a while and concluded that it can sometimes be helpful to force a person to look at what they are doing and reevaluate their life's direction.

By the early 1960s HP manufacturing divisions had multiplied. Those that had split from the mother company to other locations took with them the HP part numbering formats. But a number of companies had been acquired and these had entirely different numbering systems. These new acquisitions joining HP tended to use many identical parts in common with HP divisions but with different numbers. The difficult decision was whether the acquired companies should use the same numbers that HP divisions were using. One strong factor in favor of common parts was our global service and repair operations. Having a single parts documentation system was highly desirable. But, without a careful, technical review it was hard to be sure similar parts were interchangeable. So it would take a significant effort to merge the numbering of parts to one system company-wide.

After a careful analysis we concluded it was economically advantageous to convert all parts and components to a common numbering system so that we could get maximum quantity advantage from our total corporate buying. The conversion and the resulting higher usage with suppliers would give us more leverage on pricing and also on any issue of quality. This decision to merge to a common numbering system also meant that new parts being set up anywhere in the company had to be screened by our materials engineers to see if we already had that part set up, or if we needed to set up a new number.

Hal Dugan, Materials Specifications Manager and a various delegates from Materials Engineering were given the task of going to all of our acquired division and converting their numbers to the HP common numbering system. They went to Moseley in San Diego, F&M in Pennsylvania, Boonton in New Jersey, and Sanborn in Massachusetts plus others over time. The materials engineers played a huge role in determining compatibility before a number was changed to an HP part number. It was an arduous task, but greatly increased the volumes we could commit to our suppliers. Higher volumes gave the manufacturers longer production runs and substantially lowered their cost, a good part of which they passed along to us.

In addition to the conversion of numbers, Larry had the materials engineers develop a listing of preferred parts for use by design engineers. This also helped to focus product design on using fewer, more proven components. This helped increase our purchasing volumes and made quality management easier.

|

Hank talking with Bob Sundberg |

The last missing link was bringing in from all divisions their annual forecasts of part usage. With some effort we got these and with these forecasts summarized it was possible to present our full annual usage volumes to multiple vendors for competitive bidding.

The establishing of a strict business-like relation with vendors, the dismissal of traditional purchasing agents, moving the placement of production purchase orders to Inventory Control and now the completive bidding managed by materials engineers was very disturbing to Bob Sundberg, my direct boss. He had established excellent relationships with most of our old line suppliers and distributors. Now they were all being subjected to less personal contact and competitive bidding. This was so uncomfortable for him that he felt he had to leave HP. When he left I was asked to take his spot as Corporate Materials Manager. It is not the way I ever hoped to get a promotion. He and I had talked through the direction HP had to go several times, but he did not agree with the direction. I had hoped we could work through his distress, but he never got comfortable with the proposed changes.

My new job now had not only the responsibilities for corporate purchasing by materials engineers managed by Larry Johnson, but added the departments of Inventory Control managed by Dick Were, all the Stock Room personnel and processes, plus the receiving and shipping departments, managed by Al Spear, Material Specifications managed by Hal Dugan and Logistics, managed by Rod Ernst. This totaled something over 400 people.

Bob Sundberg had a nice office in the corner near the entry of Building 3, with glass windows, an attractive desk and chairs and had a large, artistic map of the world on one wall. I had learned the value of sitting closer to the troops, so I kept my gray desk and sat outside with the rest of the group. We turned Bob's former office into a very nice conference room.

The group began to collect worldwide component usage projections from all HP entities giving us substantially larger purchase volumes. This collection process was formalized and made routine. With this global usage information Larry Johnson's Material Engineers began to get competitive bids and place contracts which all divisions could procure against and have their orders shipped directly to their sites. All divisions began to benefit from the whole company's usage volumes. I was astounded to see how much lower the unit price bids were for these larger quantities.

As these new lower prices began to work their way through the system I noted on the company Profit and Loss statement that the material component in our cost of goods sold actually dropped 2 percentage points and this went directly to the bottom line. Higher purchasing volumes also gave us a hidden benefit, of greater leverage over quality, reliability and availability.

It was challenging and fun to set the framework for our large Corporate Purchase Agreements and to rework HP's purchasing terms and conditions which were preprinted as "boiler plate" on the back of our Purchase Orders. But by far the most interesting and complex contract that I worked on was the one for Al Bagley. It covered the development and purchase of a cesium beam tube from Varian. The tube was to be the heart of HP's highly accurate time standard instrument. I must have had more than a dozen sessions with Al to reflect his wishes. When the contract was done, as I recall, it had unique development milestones, penalties for tardy performance, tight quality specifications, quantity estimates, price/volume formulas and to top it all off HP ended up with ownership of the patents for the tube. Bagley was a genius at whatever he did. This very successful product provided a giant step forward in extremely accurate time keeping.

|

|

HP Memory Collection |

HP Memory Collection |

More Information |

Correlating Time from Europe to Asia With "Flying Clocks" Photo Courtesy of the Hewlett-Packard Company |

This incredible time keeping instrument was accurate to plus or minus a second in a million years, or some such extreme precision. The accuracy prompted Len Cutler, the project manager to send engineers around the world to compare the time standards of major developed countries. Lee Bodily was asked to go to Boulder Colorado to set a 5061 A to the U.S. time standard. From there he flew on to London to make the first comparison. By the time he arrived at the National Laboratory where their time standard was kept the instrument had been on batteries for longer than Lee wanted. If the instrument lost power he would have to return to Boulder and start over again.

When he got into the UK Labs Lee told the supervisor who received him that he was very anxious to plug in his instrument before he lost battery power. The supervisor said, "Sorry old chap it’s Tea Time and we will plug in after that." When the supervisor left for tea Lee skipped and tore apart an English Power socket and hot-wired the 5061A to the raw wires now hanging out of the wall. Lee had a higher priority than British Tea Time.

In Germany the reception conveyed a little skepticism and after the German time keepers were briefed on the traveling clock, Lee was told to wait and that they would do the measurements themselves in their secure labs. They finished and brought Lee’s clock back and declined much further comment.

In Japan the measurements went well, but Lee was thrown into a mild panic when a nice woman came in to scrub his back while he was bathing.

The whole trip was a cultural awakening for a western farm boy, turned engineer.

One day in about 1964, I noted that doom sayers in the Wall Street Journal along with other trade journalists were forecasting that a major copper shortage was just about upon us. We looked at the major copper components that we depended upon that could become scarce. Among them were transformers, coils, power cords and other wire products, etc. We tallied up an investment in a 6 to 12 month inventory of these components. It was not a small sum, but probably under $100,000. When I proposed to Ed Porter that we increase our stock of these items he suggested we talk to the Management Council and all there agreed we should go ahead with the protective purchases. The orders were placed and received. The purchases kept HP quite well supplied when the shortage did materialize.

During this copper shortage was the time that a lot of the light bulb manufacturers converted the base of their bulbs from a copper alloy to the gritty aluminum that we often get now. Also some effort was made to change high-tension electrical transmission lines from copper to aluminum. This didn't work out too well.

A couple of years later I was in the warehouse talking to Al Spear and noted a few dusty pallets in the very high racks and asked what they were. He said they were transformers and coils (largely made of copper) that had become obsolete. We didn't guess right on everything. It hit me that being safe had its risks. But at least we got through the crisis and ended up with some valuable scrap.

One night when most people had gone home, Bill Hewlett came out of his office, which was close to our area, and stopped at my desk. He was trying to estimate something very difficult and wanted to know the weight of water. I had some reference books but we didn't find what he wanted. I told him that I thought that a gallon of water weighed about 7.7 lbs. He nodded and thought for a while and seemed to remembered an old childhood rhyme and started back to his office muttering, "A pint's a pound the world around." I have no idea what he was working on.

HP's recently acquired Sanborn Company in Waltham, MA had a very large sum embezzled over the period of a year or so. It appeared that the loss involved their materials department. As a result I went back to Waltham with an inventory person, prepared to stay until the problem was sorted out. Prudent accounting and inventory control normally helps protect against such fraud, but with two collaborating, they can often circumvent the protections. One person ordered twice to get double the quantity of parts needed, then buried the second order after it had been paid. A second person in receiving pulled out the extra materials and then they resold it. Once it was figured out we suggested some process changes to Bruce Wholey who was the new division general manager. A problem like this never cropped up again in any division that I'm aware of. Merging another company into HP takes time, a lot of work and serious trust building with employees to instill the ethical integrity and high standard that HP had come to expect.

One day there was a real commotion several desks away. There were screams and shouts and a flurry of activity. The next thing that I saw was Dick Were heading for Executive offices with a flaming waste basket in his hands. With flame flaring into the air he went straight into Hewlett's office and out the rear doors to a private patio where he could set it down and put it out. Bill joked that this was the ultimate in an open door policy.

Rod Ernst, our logistics manager came to me and said that he had an idea that he thought could speed our shipments to customers by a week and at the same time lower the shipping costs. He called it air freight consolidation and explained how it would work. An air carrier and many different local truckers at the destination end had to be contacted and persuaded to perform but it looked very good. Bay Area divisions had to be persuaded to pool their shipments to consolidate them by destination before going to customers. We worked out all the relationships and Rod put the air freight contract together, initially with Flying Tigers and somewhat later with United Airlines. It cut our average shipping time from 14 days by truck, to less than 7 days by air freight and short haul trucking. It was often as fast as two days. As I recall the costs were only about 90% of what they had been by our standard ground shipment.

These were great benefits for customers and for HP. |

| With HP's growing truck freight traffic, our logistics people launched an airlift program that saved money and a LOT of shipping time to the East Coast. From Measure Magazine, September 1963 Courtesy of the Hewlett Packard Company |

Al Spear was the supervisor of the main company Stockroom. He worked out a system of conveyor belts that delivered requested parts to the production lines. They ran through several of the Bldgs 1-6 complex, each building had 2 or 3 floors each with a little over 50,000 sq ft per floor. This replaced loaded pallets delivered with hand trucks and forklifts and helped to increase the speed and accuracy of material delivery to lines where HP products were assembled and tested.

The unmovable DEADLINE of month end always created a flurry of activity throughout the company. Sales Engineers closed sales as months ended, scrambling to meet their quotas and pad their commissions. Some of our customers had expiring budgets at month end, so they pushed out purchase orders before funding expired. Somehow the HP manufacturing pace picked up at month end to meet production plans and quotas. HP's top management was always concerned about what got out the door at month end because only the items transferred to a carrier could be counted as a "shipment" in that month's P & L statement. These factors worked together to create a huge crunch in our shipping department at month end. They were a little like the boiler room guys in the Destroyer story. Everything was coming down on them, but they had no idea what was coming, or how they fit into the total picture. They had no easy way to even know the dollar value of what they shipped.

With this in mind I started taking them daily order numbers from Maria Bilzer's report to give them a clue what might be coming soon, and secondly got the daily dollar value of the goods they had shipped. When a top manager came by and wanted to see how we were doing the shipping clerks had the numbers. Their commitment to getting everything possible out the door increased dramatically and they even began to work on the truckers, who picked up our finished product, to come a little later in the day, or to come back a second time. The destroyer captain was right, it pays to keep your crew informed.

HP had a superior recruiting program for engineers. These recruits constituted the lifeblood of the Company’s product innovation and hence our revenue stream. It was a very well-coordinated effort.

As new Divisions were being formed, experienced people were badly needed to manage and supervise production, materials, accounting, marketing, EDP and other areas. Good people for staffing all the new divisions were in desperately short supply. It was clear that there was also a need to recruit good people for administrative areas. I talked to the Personnel leaders and told them that I would like to mount a recruiting effort to add about a dozen potential first line managers and supervisors and that I would work out a rotational training program for them. I must have also gotten the approval of Bruce Wholey or John Young, but I don’t recall if I did or not. We did successfully recruit a dozen or more good potential leaders from San Jose State, Cal Berkeley, Stanford and a number of other schools. We laid out about a 9 to 12 month training schedule for each of them, some started in Materials, some in other functional areas and rotated on from there. It was a very successful effort. I don’t recall that any of those hired ever made it through 9 months of rotations. They were picked off well before that. If memory serves me correctly, Jim Brownson and Al Steiner among others were part of that effort.

In my early days at HP I had a few occasions to travel in the U.S. and Europe. Wherever I went the HP people were gracious and helpful. Generally in a short time we could resolve any problem that needed to be worked out.

I was a pretty naive traveler. On an early trip to Europe Colette was able to accompany me. Her parents had graciously come to stay with our children. Together we had had some close calls catching airplanes, so for this trip we went early to SFO for this European flight. At the airport I went to exchange some money into German Marks and they asked to see my passport. Yikes! We had both forgotten to bring our passports. Colette's was at home and mine was in my desk drawer at HP in Building 1.

We had been dropped off at the airport so we had no easy transportation to go back for the missing passports. Nick Kuhn was our neighbor directly across the street. It was a Saturday and I reached Nick on the phone at home and told him of our dilemma. He was willing to help. I started to tell him how to find the emergency key into our house to get Colette's passport and he stopped me and said, "Everyone knows where your spare key is." Then I tried to describe how to find my passport at HP.

He found Colette's passport quite easily, but at HP the guard crew had no idea where to find my desk (the HP phone book just had building number and floor). Nick being a resourceful fellow dialed my phone number and wandered through Building 1 until the ringing phone brought him to my unlocked desk.

Nick delivered our passports to me at the airport and though we had missed our originally scheduled flight we caught one about 3 hours later. Fortunately security was not the big issue that it is today and with Nick's help the recovery was fairly smooth. Once in Europe HP meetings went well. Colette was very courageous and had the adventures while I was at work. On her own she took the train to Heidelberg for a day and then lost her way back. Finally a kind English speaking German helped her get back to our hotel in Boeblingen.

Then in Grenoble she ordered a luncheon meal at our hotel. She had grown up in Canada and had studied French for almost 5 years so she was more comfortable here than in Germany. As she studied the menu she spotted Ris d'Agneau and knew that this would be some dish of lamb and concluded this would be safe. When she was served it turned out there was full quivering brain of lamb on her plate with an almond on the top. Her stomach turned and she knew that she could never eat it. As sometime happens in nice European restaurants the waiter hovered very near to see if she enjoyed her meal. He was also trained not to bring a bill or menu back again until this course had been finished. She carefully ate the almond off the top of the brain and then gradually spooned the rest of the brain into an envelope in her purse when the waiter's back was turned. And finally she had done enough that the waiter brought the bill and let her escape.

On a trip in the U.S. I recall one morning in Loveland, Colorado stopping for an early morning breakfast at a small restraunt before heading into our plant there. To my surprise Dave Packard, Bill Hewlett, Barney Oliver, Noel Eldred and a few other HP leaders were there. We ate and visited. The Leaders were just returning from NYC where they had held an HP Board of Directors Meeting. When we were done eating Packard picked up the bill for all of us, about 8 people. The total was $24 and when he saw it he said "We are going to have all of our meetings here." I suspect the cost of this meal was very different from the bills he got in New York City.

In Germany I had worked most of the week at GmbH and still had more to do so I stayed over the weekend. On Saturday Hans and Heiki Vogel took me on a wonderful excursion around the area and graciously translated all the needful explanations. The next day I told them I would go on my own and try not to get lost. I went to Church there and met a very nice German family who invited me to their home for dinner. I had had one quarter (shorter than a semester) of German in college and they had a young daughter who had taken some English in school. It was interesting that we could talk about a wide range of things; from governrnental differences to cowboy movies, but it took a lot of hand waving and picture drawing. It was a warm, wonderful afternoon.

Leaving Grenoble I recall getting a ride to the Lyon airport with Angelo Carlessi as we were speeding down the motorway Angelo decided it was too hot and started to take off his overcoat. I leaned over and offered to steer the car. Angelo said, "No, no, it's OK I am steering with my knees." Happily we survived, but I was never sure we would make it. Later in the Telecommunications area I did a great deal of traveling through North America, Europe and Asia to meet with our telecommunications managers around globe. It was rewarding to be with them face to face to work out solutions and plan future directions. As mentioned below Dean Hall spared me from excessively frequent travel.

Back in 1958, John Young was a promising young Stanford MBA Graduate who accepted an offer to work at HP. After establishing himself in HP for a couple of years he was assigned to negotiate the purchase of most of our Sales Representatives. He did this well and 13 of the 15 national Rep organizations agreed to be acquired. HP then organized those sales representative organizations into 4 U.S. Sales Regions and similarly one region was developed in Europe. One benefit of the acquisition was that the new HP Sales Offices no longer handled non-HP products.

|

| These two photos show the ASR 35 we used for our data acquisition, transmission and printing functions. Pictures courtesy of Youtube |

With the Sales Representatives organizations becoming a part of HP, Bud Eldon, the current systems manager, saw that sales orders no longer needed to be typed twice. We could capture the data once in the sales office and let that data flow through the rest of the company without re-entry. The SCM machines had no data transmission capability and the best device at that time that could transmit data was an ASR33/35 teletype machine. ASR stood for Automatic Send and Receive. This machine could punch or read a paper tape, and print a document from a tape or from the keyboard, or from a transmission.

These machines were used to create a digital copy and hard copy of an order. The digital copy on tape could be transmitted at the speed of about 60 characters per second or about 500 bps. These teletype machines were installed in the field and factories to transmit orders and shipment information for the company. Carriers were paid by the character for transmission. Field offices kept paper tape copies of each order they entered and when the factory notified them of shipment, the sales office pulled that order's paper tape and used it to create an invoice to the customer. These teletypes were the beginning of our data transmission activity.

As the first few companies moved into The Stanford Industrial Park in the later 1950s (HP being one of those) it became clear that the Park was going to expand rapidly. There were large reserves of Stanford land that had been designated for leasing to industrial businesses who wished to locate here. At that time, the City of Palo Alto and Santa Clara County realized that the existing two lane residential road called Oregon Avenue was going to be totally inadequate to carry the traffic that would develop. So plans were made to provide a link from highway 101 on the East, through to the Industrial Park and then eventually connect to the planned interstate highway 280 in the West foothills. The Oregon Avenue improvement planning stirred a heated debate in the City of Palo Alto, and ultimately went to a citizen referendum for a final approval.

One day I was in church sitting next to David Haight who was then the Mayor of the City. We talked briefly, when we should have been listening, and he asked softly "What should we do about the Oregon expansion?" He knew I worked in the Stanford Industrial Park, but was also a resident of the City. The proposals had extremes. One plan called for a freeway to be developed with very limited access between highway 101 and the upcoming Freeway 280. The polar opposite was to do almost nothing to the two lane road. Residents were truly worked up about the issue. The freeway solution would cut the city in half and to do nothing would throttle the City's traffic and kill the development of the Industrial Park. I whispered back to him "Widen the street, limit the cross streets and put synchronized traffic lights at the streets that cross Oregon to smooth traffic flow." He nodded and added those thoughts to a thousand other inputs he had gathered, I'm sure. In the end that's about what the city and county did.

When Oregon Avenue was widened to make Oregon Expressway all 90 of the houses on the South side of the street had to be removed. Colette was driving me to work one morning so that she could keep the car for the day. As we drove down Oregon all of these houses were for sale to be moved. The prices were pretty low and I joked with her saying that if you bought one of these you could probably make a fortune.

About 10:30 that morning I got a call from Colette who calmly told me that on the way home she bought one of the houses. I was dumbfounded and finally asked her how she proposed to pay for it and where she was going to put it. She said "That's your job, I negotiated the purchase. It is beautiful, hardwood floors throughout. And not only that, it has tile in the kitchen, . . . etc., etc."

Over several weeks I talked to the Cities of Los Altos, Mt View and East Palo Alto and none would take a house moved from Palo Alto. They all said, "It won't meet our building code." Because other cities would not take it we went to the City of Palo Alto offices and looked through every property record for vacant lots. We found several that were available on Christine Drive which had just been extended through to Middlefield Road. We put a 10% deposit on one of the new lots. The selling price was $10,000 plus a $1,200 obligation for a street bond. It was a very nice lot on a nice street. We had real qualms about dropping an older, smaller moved house on a street of this quality.

It was shortly after we bought the lot on Christine Drive that a realtor who had been looking for lots with us called and said that he had found some lots that had just opened up on Wintergreen. We looked at the street and it was perfect. A creek on one side created shallow lots, maybe only 50 feet deep, but across the street the new lot we were looking at was normal size and it backed up to some older homes that were a good match for our moved house. We bought that lot. It is hard to get through the red tape and permits to build a house, or anything else in Palo Alto, but moving a house within the City is ten times worse. Hearings, public notices, variances, council meetings, detailed plan reviews, it was a nightmare. But it finally got approved and the house was moved so that we could fix it up and landscape it.

|

| The moved house in its new location: 810 Wintergreen |

After it was moved we found renters for the house. After about a year it became clear that I didn't have time to be a landlord. Work at HP, church leadership assignments and family used all the time I had. So we sold the moved house for just about what it had cost us. Lockheed, who was a huge employer at the time, had a big layoff and we were lucky to break even on the sale. So we didn't get rich as we foolishly expected, but we did end up with the lot on Christine Drive, where we built a new home in 1964 that would hold our 4 children and the 5th that we were expecting and eventually four more.

|

| Our family home built on the "extra" lot on Christine Drive |

|

While in Materials Management I reported to three different managers. First was Noel (Ed) Porter. He was great and almost never bothered with what we were doing. Occasionally I would get a little 3 inch square note, typed on his own personal, manual typewriter, which would have a comment, or request and was always signed N.E.P. That was about it.

Next Manager was Bruce Wholey who managed the Microwave Division (before he moved to Waltham Division). Bruce was very interested and attentive to what we were doing. He would come by a few times a week and share any news, or instructions that he wanted to pass along. When he was done he would sit a bit longer and look at me with steady blue eyes and say nothing. This would start me scraping for other things that I could tell him. I always gave him more information than I intended. It was an interesting silent interrogation method.

My Last manager in Corporate Materials was John Young. He had taken over from Bruce as the manager of the Microwave Division. He was good; insightful and like Ed Porter we didn't see him too much. It was John who sensed when it was time to give me a new challenge as I had finished the things that I felt needed to be done in the Materials area. One day he said to me that Gordon Eding would like me to come with him to Datamec. I was very happy to work with Gordon and get some first hand Division experience.

Datamec was a small computer tape drive and disk drive manufacturing company that HP had just acquired. The disk drives were more in development than in production at the time they joined HP. Some of their managers left shortly after the buyout and Gordon Eding was chosen from HP to be the Division General Manager. He asked me to join the division to be the Finance Manager. In most companies this position would be called a Division Controller, but HP had no controllers, because Dave Packard didn't think that a finance person ought to be exercising much control in a technical company. After Packard later gave up the reigns of the company a few controllers did creep into the landscape, but I don't think the substance of things changed.

As sometimes happened when HP bought a company, the acquired company got hit pretty hard with corporate overburden. First of all, most of Datamec's tape drive sales had gone to Digitial Equipment Corporation (DEC), a successful mini computer manufacturer but a direct competitor with HP computers. So a big part of Datamec's customer base pulled away after the acquisition. Secondly, HP's corporate surcharge and HP Lab overhead, plus more elaborate employee benefits were crunchers for the small company. Thirdly, they had to bear part of the expenses of part number conversions and changes to HP'S quality, engineering, accounting and production standards. This was a new perspective for me to see how heavy these burdens felt from the divisional perspective.

I traveled around the U.S. with Tom Tracy, Datamec's marketing manager, to work out termination agreements with all their Sales Representative organizations and then worked out the transition to HP's sales force. We also negotiated with HP Sales Region managers for slightly more accommodating selling terms for Datamec. Over a few months we worked out all the accounting and financial changes that had to be made to match the HP systems and standards, including forecasting and reporting processes. All this change made sense to me but the poor guys who had been with Datamec for a while were in a state of confused agony.

One day I was in the Marketing Department and I noticed that Fred Waldron, who had also transferred from HP, was looking grim. He said HP Corporate has required us to do a 5 year forecast and I don't even know what's happening next week. He showed me the areas he had to cover. I told him no problem. Corporate is going to add this forecast like a small drop into a large pool. Just take last year and add 10% per year, ask the labs if we can ever ship any disks and add a bit more in for that, take a stab at market trends, then do a little creative writing for your narrative and you're done. If the field sales force doesn't like it they'll tell us. He said, "Are you sure?" I told him that for us, right now, that will do. He looked relieved and said, "This may not be as hard as I thought." It turned out that in actual fact his forecast was pretty close.

After a year or so HP's external auditor came to do a full audit of the division. Spending a few weeks with CPAs was not really my idea of a good time. We got through it and with a little requested touchup we passed their scrutiny.

The Datamec manufacturing manager was courageous guy who was fighting off cancer. He worked nearly to his last breath. After he died, Ray Smelek joined the division to assume that role. Gradually the little division got on its feet.

Wayne Briggson had become the top Accounting/Finance Manager in HP. He was a no-nonsense, kind of leader. He kept at his desk a big red rubber stamp that said "BULL SHIT" which he used on memos and proposals that didn't make common sense. During this time HP was struggling with financial accountability. John Young was proposing a matrix system which gave product line managers worldwide responsibility for a cluster of related products. This responsibility cut across countries, sales offices and factories. It was far more complex than our old divisional model. The matrix demanded two complete sets of books, one for traditional and one for product line accounting.

This didn't match Wayne's idea of a simple straight forward business management. I think he fought this complex approach for a while and eventually left the company. (I was not close to this and I'm not the best one to report what happened, except to say the Product Line accounting was adopted and came back to haunt me later in the Heart System.)

By 1968, I wasn't looking for any changes in employment. I loved HP and for the greater part had enjoyed most every assignment that I had been given. Then one day out of the blue I got a call from my friend Roger Sant who had worked with me in HP's Systems department, asking if I would consider taking a job in his current company, Finnigan Instrument. I told him I was pretty happy where I was, but that I would talk with him. Their offices were in the Stanford Industrial Park, near the fire station on Hanover. I stopped in after work one day. Finnigan made quadrapole mass spectrometers. This was a significant breakthrough from the huge, expensive magnetic spectrometers that could wipe out all your credit cards if you got too close. These products were used for: environmental testing, such as measuring pollutants in fish livers; medical measurements such as cholesterol levels in the blood stream; crime labs for the breakdown of substance traces on crime evidence; drug testing for athletes, horses, etc., and other analytical diagnostics.

They wanted me to be the General Manager of the little company, with a sizeable salary increase and an appreciable stock equity position. Colette and I deliberated long and hard. By this time we had 8 children and a high risk situation like Finnigan didn't make a lot of sense for us. On the other hand it was a rare opportunity to work in a very small startup company and help it to grow and mature. I took the offer and bid a sad farewell to a lot of HP friends and mentors.

The Finnigan challenge was exciting, but one of the first things I noticed was that just about all 30 of the employees were very distrusting. It didn't help that I had come from the outside. The prior leaders of the company, some of whom were still around, had not always been consistent, or straightforward with them. To try to work our way past this I set up a profit sharing plan and a retirement program with some company matching. The company's contribution was not large to either of these, but it was about the best we could do with limited resources and skimpy profits.

Finnigan hit a period when the production folks could not make a single functioning spectrometer and consequently could make no shipments and hence we had no income. To resolve this critical problem I sent our best quadrapole engineer to Coors Corp. in Colorado, not to drink beer, but to work with the Coors' exceptional precision ceramic machine shop. The quadrapole was the heart of the spectrometer and consisted of 4 molybdenum rods held by 2 ceramic end pieces. We had only one quadrapole left in our lab that worked. That one unit worked well in any of the unshipable units that were sitting in production. I had Mike, our engineer, pack up this last working quadrapole and any test equipment he thought he might need. I told him he should not come back until he could repeatedly reproduce a good quadrapole. After 5 working days he called and said he had the solution. The key was one critical dimension in the ceramic machining. He brought back a bunch of good ceramic end pieces which held the four rods and we were off and running again.

The valiant, but shorthanded engineers at Finnigan had worked hard to come up with a new product or two. One new design got pretty well functional, but it looked like a lab bread board so I called Bob DeVries, a friend at HP, to ask if he would consider a small project after hours. He graciously agreed to help design a product package that would look like it had been made in a factory. When he got through it looked great. Unfortunately it never developed a great market to match its looks.

Many of our customers were interested in more sophisticated measurements. This could be done if a gas chromatograph was coupled with our mass spectrometer. With some effort that integration was accomplished and Finnigan did successfully offer a GC/MS which was well accepted.

After I had been about 2 years with the little company, Federal funding was cut off for many of the agencies that funded the purchase of our product. NIH, scientific grants, environmental projects and more were all slashed. Orders dropped like a stone and it was necessary to lay off a good share of our small crew. I decided in the process to lay myself off. There were original investors that could manage what had to be done in the company. They were good skilled people and better able than I to help the company weather the storm.

I learned some important things during those two years. I had taken for granted the people of HP with their loyalty, trust and somewhat selfless collaboration. It was clear that was unique and hard to replicate. I was also uncomfortable at Finnigan when I could not pay bills and keep financial commitments in a timely manner. A single product company is riskier and less stable than one with multiple product areas and being dependent, directly, or indirectly on government funding doesn't make for stability. Also, small companies had no central support services, of the kind I had come to expect at HP. Nearly everything you needed you had to do it for yourself.

Not everyone was happy to see me come back to HP. One fellow in the Materials Department had felt that the changes I had initiated were too severe and not people oriented. He went to Ralph Lee, who had replaced Ed Porter as VP of Manufacturing, to see if he could stop my return. In spite of these objections, Cort Van Rensselaer, with encouragement from Matt Schmutz, made me an offer to return to a job in the Manufacturing Systems Group under Cort. I was very grateful for their support. At this time each major function, Manufacturing, Marketing and Finance had its own Systems group.

Matt Schmutz, the EDP Manager, with Cort's approval, told me that I should work in his computer room to get a feeling for computer processing. This sounded like a good idea. My first assignment was to do the card sorting for a bill of materials explosion. Products to be built had to be exploded into its component parts to be purchased or manufactured. To do this explosion the quantity of each product scheduled to be built was multiplied times the component parts needed in each unit. There was a deck of cards for each instrument to be built with the component quantity needed. Now the task was to re-sort all these instrument decks by part number and assembly number to give the total quantity of each part to be purchased, or assembly to be fabricated. When every deck for every product was re-sorted into component part number the computer could tally and print out a quantity of every component for all the planned production runs. This was essential because HP products used so many components in common

The cards to be sorted made a pile well over 20 feet high, but only a foot or two at a time could be loaded in the sorter. Part numbers were mostly 8 digits and a few fab parts were longer. This meant that the entire deck would need many passes through the sorter to put the cards in their final part number sequence.

I started in the morning and had been sorting for several hours when there was a distraction. When I returned to continue sorting, I grabbed the wrong pile of cards and instead of continuing the sort I had instantly shuffled the deck. Ugh! Matt came in to see how I was doing and I told him what had happened. He smiled and said, "You've done quite enough for the day. We'll clean this up." I was never invited back and I never asked to return.

Cort asked me to develop a system for HP to HP orders where one division, or entity buys from another. There was a high volume of these internal orders and yet there was no systematic way to place these orders or to get credit back to the selling division. The high volume of these internal orders was spurred by the creation of new divisions who took product lines from established divisions to new division locations, both domestic and foreign. Cort saw the rapid growth of this activity and knew that we needed some systematic way to take care of the need. He suggested that I talk with Bill Johnson who headed Marketing Systems as he was working on a new sales order processing system called Heart. Learning what processes he was planning to use for moving orders from customers to product divisions might be helpful in handling these internal orders.

Bill gave me a detailed description of the Heart system and the sales order format and flows that they planned to use. With some adjustments I employed that order system for internal orders and then initiated it within the company, globally. This IOS (Internal Order System) initially used multi-part forms and the company's teletype transmission system, but was designed to use the computer based data transmission system (later to become Comsys) which was in the process of development.

With the IO System design completed, Cort asked if I would go to the Customer Service Center in Mt. View, CA, from which all customers and HP repair centers could buy replacement parts. He said they were in need of a computerized inventory management system. I was there for about a year working with Clyde Francis who had a fantastic knowledge of how their manual parts systems worked, and also the parts of the inventory system that needed to change. That system got designed, programmed, installed and was working quite well at the end of the year.

|

| This is a Demonstration of the new Customer Service Center computerized inventory control system |

I remember David Packard coming home from his service in the Pentagon as Deputy Secretary of Defense. As he came through the Customer Service Center where I was working, he had a friendly greeting and I asked him how it felt to be back. He said, "It's nice to be back where you can get something done."

In Packard's time away in the Department of Defense, speed bumps had been built into the parking lots and perimeter roads all around the HP Stanford Park complex. They were a pain. When Dave saw these he ordered them to be taken out and said, "These are physical symbols of lack of trust in our employees. We do trust our people and we are not going to have these damn bumps everywhere."

Another thing that had developed while Packard was gone was a gradual buildup of our short-term borrowing. This was short-term debt built up primarily to finance the cost of our operations: handling rapid company growth, purchasing materials for manufacturing, financing our accounts receivable as sales grew. Our leaders concluded that it would be cost effective to replace this short-term borrowing with proceeds from an HP Bond issue. All the work had been done for the issuance of bonds and a prospectus had been printed and distributed. We were just days away from the market placement of the bonds.

This troubled Dave. He didn't like debt and didn't feel this was the right way to finance Company growth. He stopped the Bond issue dead. Then he scheduled the "Give 'em Hell Tour" to every major field sales office and every factory. His messages were simple. To factories it was "Cut your inventories back to a reasonable, well planned level." To the field offices, which created invoices to our customers for goods shipped and then collected the receivables; his message was "Tighten up your collection processes. Bring in the money owed to us faster." He added the exclamation point to both field and factory that if they couldn't do this, he'd find someone who could. He was very direct and forceful and when local managers saw him coming, they would murmur to their team, "Here comes the old charmer." After the first couple of visits the word was out and things changed dramatically. Short-term borrowing virtually vanished overnight and there was no more need for a bond issue.

Working in Cort's systems group was a great experience. He had a rich background in HP and most recently had been in Colorado Springs where he was the Division General Manager. He came back to Palo Alto to head the Information Systems and EDP functions. As the Senior systems manager in the company and had the experience and vision to move HP's processes forward. Matt Schmutz, who headed HP's EDP department under Cort, had been hired back into HP by Bud Eldon, the immediately prior Systems Department Manager, to direct the conversion from the SS90 to the IBM 360. This decision to switch computers was a good move on Bud's part as our processes were becoming more complex and skilled support from our vendor was more critical. Matt was a good friend that I talked to often. One time we were talking about an upcoming party for the group. I mentioned that I had a conflict and couldn't come. Matt said with a smile, "That's great. It always makes me nervous when I'm slipping away into incoherence and I know you are going to remember everything in the morning."

Later Matt moved to the Business Computer Group and took on some major responsibilities for them. Sadly he developed serious cancer. I visited him in the hospital near the end and asked if I could do anything for him. He said, "Watch out for my son." His son Bill was a great young man, but had taken longer to find a direction in life than Matt would have liked. He came into my Communication Department under Luis Hurtado-Sanchez . He established himself there quite well and found some work areas that he really enjoyed.

Bill Johnson, who succeeded Bob Puette as the Marketing Systems Manager and Heart System development manager, talked to Cort and asked if he could recruit me to his department. I had worked with Bill when I was developing the Internal Order System. Cort agreed to the transfer as the inventory system at the Corporate Parts Center that I had been working on was up and running. Johnson felt he was having some challenges in his telecommunications area and asked if I would manage it. This was a small group of about 6 people but their work was to be the backbone utility of the order information flow within the company. The Heart system was still under development, but before it could be deployed it was going to need a superior data transmission capability in order to function. The Internal Order System that I had worked on was designed to use this data transmission capability as well.

|

| The HP 2116A started life as an engineering computer, but was adapted for Time-Share data handling, which made it ideal for our data transmission service. |

An interesting historical note: In about 1966 Bud Eldon, as Information Systems Manager, suggested the possibility of transmitting sales order information between 2116 computers to replacing the ASR 35s which he had deployed. There was some management skepticism about this possibility. Bud also, before he left the department, hired Bob Puette and a number of others to do Operations Research. Dick Hackborn was hired into this group on a part-time basis while he attended Stanford. Out of this the seeds of the Heart System and Comsys were planted.

The invitation to work with this group looked very interesting and I had had some exposure to the planned data transmission system already. I liked Bill Johnson who would be my boss, as well as Rich Nielsen, Gene Doucette, Bill Taylor and the people involved with the Telecommunications group, so I readily agreed to the move.

Bill Taylor and Gene Doucette were working with telephone companies and telephone equipment manufacturers. They looked for ways to lower our telephone line charges and negotiated telecommunication equipment contracts. They were responsible for PBX selections which were complex devices made by AT&T, Northern Telecom, Rolm and others, used at each HP site to receive and reroute inbound and outbound telephone calls.

Paul Storaasli in the Telecommunications group was working now with Rich Nielsen who had joined Howard Morris in Programming. Rich had then taken over the project when Howard transferred to Cupertino. Rich was working on the HP 2116 coding to give HP a better, faster and more accurate method of transmitting data with the use of computers rather than teletype machines. With some hard work Rich developed software to generate fast, reliable data transmission between two 2116 computers. Testing showed that this was much faster than the teletype machines we had used and was free from bad line errors which we got with teletype. We did some calculating and determined we would need well over 100 computers phased in over time to set up the network. This was a very large investment, even though it was HP equipment. We also needed to buy modems from an external vendor and these in total were quite costly as well.

I took our investment analysis to Bill Johnson and he said, "Let's go for it." He and I talked to Bob Boniface who was now the Exec VP over HP's worldwide marketing. He thought it looked good, but said it was a large enough investment that we should get approval from the Management Council. I got out the paper pad and felt pens to make a few panels to explain what we were doing and what the investment looked like. There was an offset in cost from the replacement of the slower teletype machines and their relatively high transmission cost. In addition the new network opened the possibility of transmitting additional kinds of information through the HP computers. We got quite an enthusiastic approval from HP's managers. Packard said this should be a product. It was a different and interesting use of HP computers which up to that time had been used mostly for technical engineering work and very little for business applications. We placed orders for the HP computers and scheduled them out at the pace the Cupertino Manufacturing Division could sustain and still serve paying customers. We matched this shipment schedule to our installation plans.

Later the Comsys data transmission system did become a product, the HP 2026. Some systems were sold but it never became a big seller. Other companies found it difficult to deploy and manage the system in the way that HP had done.

Commercial telephone lines at that time were very expensive compared to the current time, 2012. We could not broadly afford the expense of dedicated leased telephone lines. As a result our data transmission was planned for the use of dial-up lines. This meant you had to pick up a phone, get dial tone, dial the remote number, get a confirming modem tone and stick the telephone hand set into the modem and start computer data transmission. Standard modem speeds were 1200 bps. We were testing our transmissions with a 2400 bps modem and it worked OK over dial up lines.

Just as we were about to order more than 40 of the 2400 bps modems, Gene Doucette and Bill Taylor found a reliable vendor, Paradyne, who offered a brand new 4800 bps modem at about the same unit price as the ones we had been testing with. A modem which was 2 times faster was like gold. We could get our data through faster with lower telephone line cost, which was charged by the minute. We ordered the faster modems. The Paradyne modem also had a slow speed reverse channel that could function at the same time a full transmission was going forward. Rich Nielson included a clever error detection and correct scheme using this reverse channel. Data being transmitted was assembled into packets (a set of a couple of thousand characters) and at the end of each packet the sending computer calculated a sixteen bit check sum. The receiving computer read the incoming packet and did its own calculation. If the sending and receiving calculations matched the receiver would send back over the reverse channel an acknowledgement (ack) that the transmission had been received correctly. If the calculations didn't match because of a line error, the receiving computer would send back over the reverse channel a non-acknowledgement (nack) and the sender would send that packet again. This gave us virtually error free transmission, even over marginal phone lines. Using the modem's reverse channel avoided having to stop the main transmission to send back confirmations or error messages. This was another important transmission speed advantage.

Because dial up lines for transmission were available everywhere in HP's worldwide organization we could move ahead quite quickly. As we received equipment we started up the first Comsys transmissions.

When data was entered at all the HP locations the teletype machines were still what we used initially to capture data on punched paper tape. The tapes were very awkward to label, store and handle. In all computer sites, the walls were covered with hanging tapes and in many sites clotheslines were installed to create more hanging space. In at least the larger sites, the paper tape was input to the 2116s where the data could be stored on magnetic tape in preparation for faster computer to computer transmissions.

Our computer data transmission system was given the name of Comsys, short for Communication System. As Comsys became broadly deployed, a key bottleneck was the entry of data to paper tape and then feeding the paper tape into the HP 2116 computers. Teletype machines which produced paper tape were so awkward that Paul Storaasli and Terry Eastham were determined to find a manufacturer who could supply a terminal with a keyboard and a CRT display that could input directly to an HP2116. Direct terminal entry to our computers also offered the important possibility of editing input making possible immediate error detection and correction on the data entered. Teletypes could not do this.

Finally we found a small company in Salt Lake City, called Beehive Electronics, that made something very close to what we needed. They accepted our requests for modification and slowly began to deliver computer terminals to us. These new terminals eliminated the teletype machines and the punched paper tapes. The Beehives were deployed in the HP computer rooms around the world. The Beehive terminals were a huge step forward, but getting worldwide support from this small startup company was a real issue. Terry often woke up at night with nightmares about Beehive support. Field reliability was improved by burning in the Beehive terminals before they were deployed.

It was a couple of years before HP developed a full featured CRT terminal, the HP2645A, which could replace these Beehive terminals. The HP product gave us significantly higher quality and much greater reliability.

|

| The Beehive terminals were replaced by the much more reliable HP 2645A. This photo shows these HP terminals assembled to demonstrate that one Comsys computer could support 64 data entry terminals as well as all transmission activities. The demo was for the people working on HP 2026, the Comsys Product. Pictured L to R are Hank Taylor, Rich Nielsen, Terry Eastham |

More Information |

The implementation of computer to computer transmission with keyboard to computer data entry started in 1972. The network was near completion and functioning quite broadly in 1973, even though the CRT terminals for input and printers for output were still restricted to the computer rooms, just as the teletype machines had been. An article in the April, 1974 Measure, "The Penny Post Rides Again" describes the broad use of Comgrams throughout the company. Comgrams were internal messages which could be transmitted over Comsys from and to any point in the company for just a few pennies. These messages were entered into Comsys in computer rooms, which then sent them forward in batches. In the receiving computer room, they were printed out and delivered by the office mail system. It took one to two days to get from desk to desk. Nevertheless at this very low cost it was extremely fast for the 1970s.

An interesting side note occurred during the time that we were up to our ears in paper tape. All over the company in computer rooms, paper tapes with order numbers written on them were hanging around the walls and on clotheslines. When shipments from factories took place these tapes were retrieved to create invoices for the items shipped. This often required cutting and splicing the paper tapes and had to be done pretty accurately or the spliced tape could jam the tape readers. Gene Doucette designed a simple aluminum block with a cutting guide and pins which matched the paper tape sprocket holes. One or two tapes at a time could be cut on this jig and then spliced to another tape with excellent precision and this prevented tape jams in the reader. Gene asked an HP traveler, probably Greg Garland, to take a couple of these splicing devices to Europe. A Swiss security agent grabbed the hapless messenger out of the customs line. They held him while they X-rayed the aluminum jigs and questioned the poor guy, threatening to put him jail for carrying secretive devices. With careful explanation he was finally released with his aluminum blocks. It was good in many ways to be rid of the paper tapes.

Outside the US, the governments of each nation kept control over all telephone equipment and transmission lines. Some countries were more cooperative than others. As we established dial-up connections to the tougher locations, their restrictions were painful, allowing only 1200 bps modems which were manufactured under their direct control. Geneva, Switzerland was a primary hub for all of HPs Europe's transmissions and was a very high volume location, but the Swiss PTT was very restrictive. We negotiated with them for some time to install a faster non-Swiss modem and their answer was always no. Finally in exasperation I told them that unless we could install a faster modem that we would move our European Headquarters to another country that was more cooperative.

I almost certainly never could have persuaded HP to do this, but the comment was heartfelt and caught their attention for the first time. They said, "Give us a minute." They came back and said that we could install a faster modem, but that it would have to be called a test installation and they wanted it located underneath the raised computer floor so as not to be visible. I asked how long the "test" would be allowed and they said indefinitely. Essentially they were saying you can have it, but don't flaunt it. We said, "Done!"

In Taiwan we were having a similar struggle with their government. As we lobbied hard for more speed they said this would be inconvenient as they were monitoring every transmission. We protested some and pushed for a trial at higher speed and they responded, "We shoot spies." We lost that round.

Bill Johnson mentioned to me one day that he was going to hire an ex-convict to help with sales statistics. The combination of sales stats and ex-convict struck me odd and I asked if he thought that was a good idea. He said he had talked to Mark's parole officer and that there was zero chance of any problem working with him. Mark had been addicted to heroin and run into some trouble with the law, but he had been rehabilitated using methadone. He was bright and fully reliable. So he came on board. There were many requests every day for special information from the Sales Stats files and Bill got the help he needed to produce the special reports.

Mark learned fast and did his work well. He looked a little different than the typical HP employee with a wild hair style, a full beard and tattoos all over, but people really liked him. After he had been around a year or so he was talking to Johnson about his love of motorcycles and when he rode one he felt absolutely free and happy. His problem was that he hadn't saved enough money yet to buy one. Bill said "Go try the HP Credit Union they'll help you." In a few days he came to work with a helmet under his arm and he proudly took us out to see his new cycle; a powerful Harley.

He loved to tell of his old days on a cycle and the trouble he had, especially with women drivers. He swore that there was something genetic that made motorcycles invisible to a woman. In one of the many stories he told, he was riding on 280 when the freeway was very new. Not too many cars were on the road and he was sideswiped by a woman in a large car. The impact tipped his bike and as it fell he eased himself onto the up side and sat on it like a sled. He was going well over 60 mph and the bike, riding on its side, spewed off a 100 foot sparks plume, while he sat on top. By the time the bike stopped sliding he was well off the highway on a grassy shoulder. The lady driver had kept going, completely oblivious to his near death experience. With some minor adjustments and repairs he was soon back on the road.

Several years after he came to HP and had his new motorcycle, he was riding a country road on the Fourth of July, hit some unexpected loose gravel, spilled his bike and was killed. It was a sad day for all of us who worked with him. It was instructive to us managers that we could help rehabilitate a motivated person, with high expectations and careful encouragement.

|

IBM Computer Room Where Heart was Originally Processed Photo Courtesy of the Hewlett-Packard Company |

While the Heart System (for sales order processing) was in the late stages of development Bill Johnson decided to leave his Corporate Marketing Systems management spot. Jack Petrak was now Bill's boss. Jack, who worked under Bob Boniface handling marketing administrative activities, asked me if I would take Bill's job and oversee the completion of the Heart development and implementation. Comsys was now fully functional and was starting to transmit some of the Heart system's data. It was also transmitting other data such as reports, data files and the company's general message flow. I accepted the new assignment.

Heart was a massive project. Chuck Sieloff who was the programming manager for Heart software as development was nearing completion said, "HP had never undertaken anything of that scale before." Over 5 or 6 years it had ground down three generations of Marketing Systems Analysts and a few generations of programmers. It used true database management that we had never used before. It had more than 100 modules all written independently that had to be made to fit together. It was so large that testing had to be done at an outside service bureau until HP bought a much larger mainframe computer. Chuck Sieloff observed, "When implemented, Heart [with its tentacles reaching into all parts of the company] became the de facto enforcer of company wide data standards, making it possible to build other applications around its periphery. Once Heart was fully implemented, I think it was viewed as a major competitive advantage for HP."

As the Heart modules moved toward completion the most demanding thing that the Corporate Marketing Systems group had ever done was to document the system for users, train them office by office, factory by factory and also train the Corporate users. This included activities like Accounting and even the data processing center where invoices and acknowledgment were now created and mailed and sales statistic reports were generated. They all needed training and new procedures to be put in place. All told it was an overwhelming project.

In over-simplified terms the Heart system created new field office and factory systems and used our IBM* mainframe computer which held the files and did the processing as follows:

Customer File: Contained information for all of our customers. Every order was passed against this file to assure correct customer number, shipping, billing addresses, tax coding and so forth. It verified the Field Sales Engineer assignment to the customer and provided coding for commission credit.

Product File: Had every HP product and option listed. It provided consistent product description and current pricing each order passed against it. It also provided approximate delivery availability. This file was also used to create quotes for customers and to produce and manage the Company's Price List. The product file had an accompanying file of configuration rules. It also had coding for worldwide product line accounting.

Sales Order Processing: Took the order from the field and accessed the customer file and product file to assemble all the correct coding for each order and provided the coding that allowed sales to be tallied by field engineer for commission payment, or by office or region, or country, or by manufacturing division or by product line. These sales orders were split to the appropriate manufacturing division for shipment. The system produced an order acknowledgement to mail to customers which verified pricing and approximate delivery dates which were taken from the Product file.

Open Order File: When items on an open order were shipped by the manufacturing division a shipment notice was sent to the Heart Open Order file and an invoice was created for the items shipped which could be sent to the customer. The data for all these shipments was passed on to HP Finance who tracked shipments to help produce HP's Profit & Loss statements and also created Product Line account for all of HP. From this processing, sales commission were calculated for field sales engineers. Information for sales tax accounting by state was generated. Unshipped orders gave an automated view of backlog by product division and product line.

Sales Statistics File: This file held all historical sales information and was broadly used for analyses of current month's sales activity and analysis of historical sales information and trends.

* Sometime later, Heart was painfully converted to run on HP 3000s. As the HP operating system became more capable and the processing power increased the HP 3000 provided an excellent computer system for Heart.