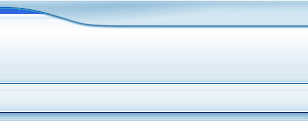

The bus ride on the four-lane expressway connecting Boulder to Denver was unexciting until we reached the top of a long rise. Then, as we passed the crest, an incredibly beautiful view appeared—the city of Boulder backed by the snow-capped foothills of the Rocky Mountains. Seeing the glorious sight in person was far more impressive than what my former teammate had shown me in his CU yearbook. I silently thanked him for recommending this school to me.

|

Two photos of Boulder. Left: Part of the university campus with some of the foothills in the background. |

It was mid-afternoon on a gorgeous sunny day. I left my luggage at the Student Union and went to the office of the head track coach to find out about housing and my scholarship. After introducing myself and handing him the letter I had received from him earlier, he looked at me with a puzzled expression. “How old are you?” he asked.

“I’ve just celebrated my 27th birthday,” I replied.

“Uh-oh. You had better sit down, son. We have a problem.” In the next minute or so, he explained what it was.

The U.S. had long dominated the sprint, jump, and hurdle events in track and field. European and Australian runners excelled in middle- and long-distance running. Some American colleges had begun to recruit foreign distance runners, who generally peaked in their mid-twenties. The college alumni responded unfavorably to squeezing out American students, so the Big Eight Conference had set an age limit for foreign students. Under that rule, eligibility for foreign college athletes began at age 18—even if they did not attend college. Therefore, when I turned 22, my eligibility for a Big Eight school ended. Somehow, no one had thought about to checking my age.

The coach felt almost as bad as I did. He had assumed that I was the same age as my friend Blair, who had transferred to CU from Dubuque earlier. Trying to cheer me up, he told me that the soccer team did not have the same restriction. “You can try out for the team,” he offered. ”But there are no scholarships for soccer.”

During my high-flying lifestyle in Toronto, I had saved only about $1,000. Out-of-state tuition at CU was $720 per semester. Room and board in the dorms cost about $120 each month. My funds would not even be sufficient for the first semester.

Fortunately, the coach thought of a way to help me.

The assistant in the electrical engineering lab had just graduated, he explained, and the professor in charge was looking for a replacement. Professor Wicks, the head of labs, was happy to find someone with circuit and test equipment experience. He hired me the same day to work there half-time. The pay was not great, but the job enabled me to pay tuition at the in-state level—only $180 per semester.

The coach also sent me to investigate the cheapest place in town to live, the Men’s Co-Op. Conveniently located at the edge of campus, adjacent to the home of the University President, the three-story house had about a dozen rooms. There was an opening in one of the double rooms for $50 per month. The cost was low because all the residents shared duties, including cooking and cleaning.

My would-be roommate, Eric, was a junior and an early hippie. A native of Colorado, perhaps he was inspired by the grandeur all around him. Maybe he was just rebelling against the norm. In any case, he told me immediately that he rarely cleaned his clothing or cut his hair. In addition, he declared that he only washed his bedding once each semester. Because this washing had just occurred, the room did not smell too bad.

As a money-making venture, he had decided to brew beer that year and had already stashed a large number of bottles of his concoction on one side of the room. Once it fermented, he planned to sell the beer for 25 cents a bottle.

Eric’s slovenly habits were probably the reason for the vacancy at the Co-op. However, I was not in a position to be choosy and felt relieved to sign the nine-month agreement. Once again, my financial problems were resolved on the first day of my arrival in a new place! [*Just as had happened in Chicago in 1960.]

With an aching heart, I had to accept that my long track career had come to its end. Even if I began to work out on my own and could again join a club the following summer, at the age of 28 I would no longer be competitive. My dream of going to the Olympics one day faded away. I decided to give up track and concentrate on making the school’s soccer team.

After settling at the Co-Op, I went to the soccer field. Although I considered myself to be in good shape, my regular one-mile warm-up jog nearly exhausted me. Others reminded me of the effect of the high altitude, and it took me a few weeks to adjust completely to being 5,400 feet above sea level. The coach was impressed with my speed and soon put me on the first team. For the next three years, I played soccer for CU. I became the team’s co-captain in my last year.

Registration for my academic courses brought an unpleasant surprise. Although my transcript showed good grades, the math professor who processed me was not impressed with my small-school background. When he heard what book we had used at Dubuque for calculus, he told me, “That book is outdated. We teach the new math here, using my textbook.” After disallowing both of my sophomore math courses, he put me in his class.

“You need to learn the Set Theory,” he said. “It’s a new method of math.” I had never heard of that term before and developed an instant dislike to the professor. His course sounded intimidating.

I no longer have the textbook written by that professor, but here is a similar “simple introduction” of the Set Theory from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. [*http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/set-theory/]

The fundamental concept in the theory of infinite sets is the cardinality of a set. Two sets A and B have the same cardinality if there exists a mapping from the set A onto the set B that is one-to-one, that is, it assigns each element of A exactly one element of B. It is clear that when two sets are finite, then they have the same cardinality if and only if they have the same number of elements. One can extend the concept of the ‘number of elements’ to arbitrary, even infinite, sets. It is not apparent at first that there might be infinite sets of different cardinalities, but once this becomes clear, it follows quickly that the structure so described is rich indeed.

This paragraph speaks for itself and explains why American students have so much trouble learning mathematics. After having been the top student in every math class I had ever taken, I struggled through both semesters of the “new math” and learned very little. Fortunately, the professor who taught the higher-level course the following year did not use the same approach and saved me from being completely turned off by the subject. By the way, in my 40 years of successful engineering practice, I never once came across a practical application of Set Theory!

In addition to the standard electrical engineering program, I also took accelerated core courses in the business school for three hours weekly. Learning the principles of accounting, finance, management, marketing, statistics, and business law was extremely interesting. How much easier it would have been to manage employees at Tanny’s Gym had I known what I was now discovering. The more I learned, the more I realized how little I really knew about how to run a business.

One business course required extensive reading. Our Business Law professor, a fascinating lawyer, asked us to read a book each week. We also had to memorize terms and events, an activity that had never been easy for me, even in my native language. Of course, I understood that a lawyer had to remember all those facts, but I preferred the more analytical homework assignments.

Perhaps the most interesting business course was Statistics. In our first session, the instructor asked the class to predict the population of Boulder in 20 years. Like everyone else in the course, I researched the past growth of the city and extrapolated it to the future. All of us received F’s for our work.

The instructor lectured us at the beginning of the next class. “You forgot to include the effect of IBM’s opening a plant in Boulder next year. Many of those employees will come from other places,” he began. “In addition, the presence of IBM will result in new startups related to computer peripherals. Re-do your work!”

Considering such a growth spurt had never occurred to us. The next week, we proudly presented our new projections but received the same disapproval from the instructor. “You did not take into consideration that the baby boomers will have more children. Do your work again!”

The following week he told us we forgot to include the effect of Boulder’s climate. “We have at least 300 clear, sunny days each year. That will attract people from those gloomy Eastern cities,” was the next clue. And so on. Every week he gave us another hint on how to improve our prediction. By the end of the first semester, we had a sophisticated model and learned much about forecasting. I wish I had kept my final result so I could see how close my projection came to the actual population of the city.

The Friday before Thanksgiving vacation, I walked back to the Co-Op for lunch and found several of the boys sitting in the living room, somberly staring at the television set. “What’s happening?” I asked.

“President Kennedy was shot in Dallas,” replied one boy quietly.

The news shocked me. The President and his pretty wife had been in the news the previous night, looking happy and healthy. “Is he OK?” I asked.

Nobody knew, but ominous news began to come from the local Dallas station. After a short time, Walter Cronkite, his voice shaking, announced that the President was dead. We all sat and stared at each other in disbelief.

The front door opened and Henderson, one of our housemates, came in. Seeing us sitting quietly, he asked what was going on. “The President was shot and killed in Dallas,” answered one of the boys.

“Well, he finally got what he deserved,” Henderson declared happily. “He should have stayed home.”

“Get out of here, Henderson, you b------!” yelled Eric angrily.

Henderson, a big beefy Texan who was also an ROTC Marine, outweighed Eric by about 100 pounds. He took a step toward Eric, probably to respond to the insult. Then, looking around and realizing that he was hopelessly outnumbered, he backed away. Muttering something about stupid liberals, he went to his room.

None of us felt like having lunch so we dispersed quietly. At dinner, Henderson apologized to the group for his insensitive remark. I did not forgive him and avoided even talking to him for the rest of the school year.

Our soccer team won the Rocky Mountain Intercollegiate Soccer League championship. We also played exhibition games against other Big Eight schools, finishing the season undefeated with only one tie. Although I preferred to play forward, the coach had me play center halfback. He reasoned that I had the speed and the stamina to guard the other teams’ center forwards, who generally represented the largest scoring threat. Although soccer games required two 45-minute periods with continuous play, I always felt that running a single 400-meter hurdle race was far more tiring. [*In those years, soccer was played in a more offensive style, compared to the midfield-oriented strategy of today. A team had five forwards, three halfbacks, two fullbacks, and a goalie.]

|

Picture of our League Champions soccer team, taken at the award banquet. I am standing to the left and slightly |

My roommate’s beer-making effort was not successful. Some nights I heard popping as his vertically stored bottles blew their lids and foamed all over. Our room developed the foul smell of a cheap pub. We had to keep our windows open for several days to take the odor away, and the carpet required professional cleaning.

When the whole brewing process was complete, he generously opened a couple of bottles to share at dinner. The brown liquid tasted awful! At first, I thought that it was only me because I had been spoiled by good beer, but the expressions on the faces of the others confirmed my judgment. The “beer” was not fit for human consumption. Eric quickly lowered his price from 25 cents to 10 cents and eventually to five cents per bottle. He could not sell a single bottle. His pride prevented him from dumping everything so he slowly drank his entire stock himself during the rest of the school year. I felt sorry for his business failure but was glad when the last bottle was out of our room.

Several Boulder residents volunteered to become “host families” to foreign students. The Sheets family selected me and invited me to their house regularly for home-cooked meals. They had two teenaged children who loved to hear about my experiences during the Hungarian Revolution. Their son, Payson, who planned to become an archeologist, had heard about Attila the Hun in history class. He was hoping to visit Hungary one day and look for the unknown gravesite of the king.

One day Mrs. Sheets asked me what my favorite Hungarian meal was. “Chicken paprikás,” I told her.

“Would you prepare it for us one day?” was her next question.

“I would, but I don’t know how.”

“Could you ask your mother for a recipe?” she persisted.

The next day I wrote Mother and asked for instructions. By return mail, she sent me a hand- written recipe. My host family mother became excited and invited several neighbors to come over during Christmas vacation for a Hungarian feast.

The two main parts of the chicken paprikás are the chicken, cooked in a broth, and the dumplings, called nokedli. Mrs. Sheets purchased all the ingredients. The recipe outlined instructions for the chicken, and I proceeded to cook it in a large pot. The nokedli required a lot more work. I remembered watching my mother make it many times. First, she would make the dough and then flatten it on a breadboard. Holding the board over the stove, she would then chop small pieces directly into a pot of boiling water. Immediately, the pieces of dough sank to the bottom. When they came up to the surface, they were ready to eat.

Somehow, I misread the recipe and put too many eggs into the dough. Instead of the expected nice, smooth texture, the dough was thick and sticky. When I began to chop it into the water, instead of small half-inch segments, large chunks of dough came off. They did sink to the bottom of the boiling water, so I was satisfied and waited. The problem was that they never rose to the top. I did not know what to do. After a long wait, I decided to fish them out of the boiling water and serve them as they were.

While I was concentrating on the dough, I totally forgot about the chicken. By the time I rescued it from the pot, it was completely overcooked. The meat came off the bones and looked very unappetizing. Not having any other choice, I proceeded to serve the meal.

The guests were extremely polite, but I could tell that the dinner was a disaster. The meat was watery and the oversized dumplings had the consistency of racquetballs. I watched our guests struggling as they tried to cut the large lumps of dumplings without much success. Fortunately, Mrs. Sheets had baked a beautiful apple pie, so at least our guests did not have to go home completely hungry. My host family never asked me to cook anything after that event.

The academic year passed quickly. I stayed at the Co-Op during school vacations, reading the law books and trying to understand Set Theory. In spite of my best efforts, I barely managed to receive a C in math. In the first semester, I received a B in Business Law and A’s in all other courses. In the second semester, I received all A’s except for a C in math again. My cumulative Boulder grade average for the year was 3.58.

I enjoyed working for Professor Wicks in the electronics lab. He encouraged me to apply for an academic scholarship. Nearly all of them were available only to U.S. citizens or immigrants with Green Cards, but he found a company without such a restriction, called Square D. I applied immediately, and Mr. Wicks wrote a nice recommendation to accompany my request. Within two weeks, I received the news—Square D had granted me a scholarship of $500 for each semester until I completed my B.S. (Electrical Engineering & Business Administration) degree. After thanking the company, I began to consider moving out of the Co-Op in the fall.

Instead of looking for full-time employment, I decided to take courses during the summer to earn more units. Some of the credits I had transferred from Dubuque had not been allowed. My double major required additional courses, so it made sense to stay in school all year round. I also continued working in the electronics lab, developing new experiments for the following school year. My days were as full and challenging as they had been during the regular term.

The only bright part of the summer was a visit from my Toronto girlfriend. She could stay in our room, because Eric had gone home for the summer. Her German nature, however, could not stand the condition of the room. As soon as she arrived, she began a major cleaning. When Eric returned at the end of the summer, he did not recognize the place. Suspecting that he would not help to keep the room clean, I let the Co-Op know that I would not be staying there for the next school year.

Our soccer team’s goalie, Dick Rumpf, was planning to move out of the dorm and was looking for a roommate to share an apartment. Dick, a German-American aerospace engineering student, and I had similar personalities and interests. The two of us began to look for a furnished apartment to rent. We soon saw an advertisement for a basement apartment, only a block away from the Co-op, in the paper. Dick and I immediately responded. The one-bedroom apartment with its small kitchen and spacious bathroom looked perfect to us. The rental price was unusually low.

Mrs. Williams, the elderly widow who owned the house, interviewed us at length. At first, she was reluctant to rent to us, because she preferred a married couple. Using the salesmanship I had learned in the gym, however, I convinced her that having two engineers in the house would be a real asset. She would never have to worry about mechanical and electrical problems. We also promised to keep the place clean and not to sneak in girls. Finally, she agreed, and we moved in the following day. As for our promises, we did keep the apartment clean.

The first night, when we went to bed, we learned why the rent was so low. Our bedroom window faced the house of the “animal house fraternity” of the campus. Loud music and party noises kept us awake. At midnight, we called the police and complained. After a while, the noise calmed down, and we managed to sleep for a few hours.

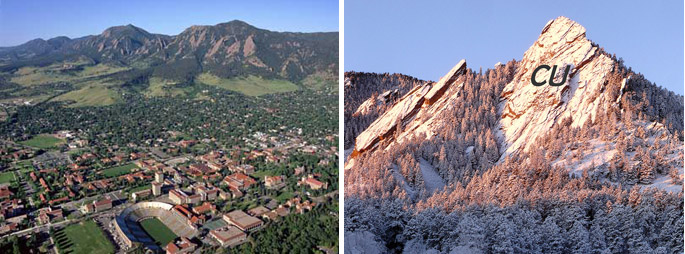

During the next week, the fraternity hosted two more loud parties. After each call to the police, the frat boys pulled back inside their building and turned the volume down for a while. Next, we complained to the Inter-Fraternity Council and I wrote a letter to the student newspaper. The day after the letter was published, two of the fraternity boys came to see us.

|

My letter, as it appeared in the Colorado Daily. It brought an immediate response from the fraternity. |

“We’re sorry to hear that our parties keep you awake,” one of them stated. “Instead of complaining to the police, why don’t you join us? We have more girls than we can handle.” “You’ll have lots of fun,” added the other.

Although their offer sounded tempting—“if you can’t beat them, join them”—we declined by telling them, “We’re engineers and have to study.” After some negotiation, we reached a mutually beneficial agreement. They would let us know in advance about their parties, so we could study in the library on those evenings and not complain. In return, we could take home their leftover party food. In addition, if they had too many girls at a party, they would invite us over to discover “what you’re missing by not joining our fraternity.” The arrangement worked well for us. We saved money on our grocery bills and had opportunities to meet sorority girls who would never have come near the school of engineering.

Although we lived on the edge of the campus, I was itching to have a car. When I mentioned it to one of the sponsors of our soccer team, who owned a dealership in Boulder, he showed me a used 1947 Chrysler. “This beauty was owned by one of our lady teachers,” he began. “She kept it in her garage and rarely used it. The car has only 26,000 miles on it and is in excellent condition.” He sold it to me for $150.

Compared to the current models, the nearly 20-year-old Chrysler looked like an old battleship. However, it was in spotless condition and had velvet-covered seats. I had wheels for my stay at CU.

Our soccer team again had a banner year, although we lost a game against the Air Force Academy. Playing against the Academy was always challenging. Although most of their players lacked soccer skills, they were extremely tough physically. The rules allowed unlimited substitutions. Three or four times during the game, their coach would send in a new squad. “Kill” was their strategy. I suffered a broken cheekbone in the game against them and had to sit out the last two matches of the season. The bone under my left eye had to be repaired with a stainless-steel wire.

Near the end of the semester, I was invited to a meeting of the engineering honorary society, Sigma Tau. Professor Wicks told me that being a member of an honorary always looked good on a résumé, so I went to the gathering. About 40 other students showed up; some of them were already members. While we waited for the meeting to begin, I started a conversation with two girls seated behind me. When one of them heard I was studying electrical engineering, she asked me what to do about her transistor radio’s volume control making unpleasant scratchy sounds. I offered to look at the radio the next day.

The four officers of the society sat at the front as the president opened the meeting. He explained the charter of the society and talked about their activities. At that point, the vice president took over. “You’ve been selected for possible memberships, based on your academic performance and extracurricular activities.” He then asked all newcomers to say something about themselves. When it came to my turn, I told the group about my long-time interest in electronics and that I had given up a well-paying job to become an engineer. One by one, all the others also introduced themselves.

At that point, all new pledges were asked to leave the room and wait outside. After a while, the president invited us back. “Congratulations,” he said. “You’ve all been accepted. Now, we’ll elect the officers for the next year.” Then he asked for nominations for president.

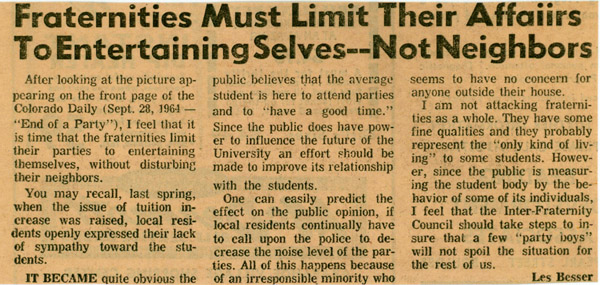

To my surprise, the girl with the radio problem, Sharon Varian, stood up to nominate me. She told the group how I had offered my help without even knowing her. She also added that my experience managing the gym would enable me to lead the group. I was stunned to hear the unexpected endorsement by someone I had just met. Three others also received nominations, but I won the highest number of votes. To return the favor, I nominated Sharon for secretary. She was also elected.

After the meeting, the former president handed me a booklet, Robert’s Rules of Order. “Study this so you can handle future meetings,” he told me. I learned many new concepts, such as orders, motions, resolutions, and more. The first meeting when I presided was not easy, but after a while, all of us learned our roles. I enjoyed our meetings and decided to become involved in the student government. By the spring of 1965, the student body elected me to be a member of the Associated Engineering Student Council. I also held offices in two other engineering honoraries: Tau Beta Pi and Eta Kappa Nu.

|

Student government photos from 1965. Left: Sigma Tau. |

I liked all the courses during my second year at Colorado, with the exception of Electromagnetic (EM) Field Theory. The subject itself was interesting: how electric currents create magnetic fields and what the effects of these fields are. The part I did not like was memorizing long formulas. There was no lab associated with the course, so we learned only the theory.

In the second semester, the professor who taught the course left for a one-week conference. A practicing engineer from a Boulder company took over instruction during our teacher’s absence. He showed up Monday and wanted to know what we had learned so far. He asked about real-life applications of EM fields. When we could not answer any of his questions, he shook his head in disbelief. “Let me explain how these fields are created, measured, and applied,” he told us. During the rest of the week, he changed the seemingly boring subject to an interesting one. Instead of learning new formulas, we began to understand the fundamentals of the topic. We loved that engineer!

At the end of the week, our class presented a petition to the Dean. We asked if that engineer could continue teaching the course for the rest of the semester. Our request was promptly denied. We had to endure memorizing yet more equations without understanding their purposes. After completing two semesters of the course, earning B’s, I had learned very little.

Professor Wicks, my mentor, had been a college classmate of a man named David Packard, and they had worked together for a while at General Electric. In fact, the professor recalled the time when Hewlett and Packard started their business and invited him to join their new venture. “I was not a risk taker,” the professor told me. “I wanted a steady job and secure monthly paychecks. Imagine what I’ve missed,” he added.

In the spring of 1965, Professor Wicks recommended that I work at HP in Colorado Springs during the summer. HP was known to support the continuing education of their employees. The University had a branch in Colorado Springs. “I’m certain HP would even allow you to take a course during working hours,” he told me. I followed his advice and applied for a summer job. One of the HP engineers who regularly visited our school interviewed me and offered me a summer job on the spot. I happily accepted and looked forward to working for that famous company.

When the second semester ended, I moved to Colorado Springs. My roommate’s parents lived in the city. They helped me find an inexpensive trailer-home rental for the summer near the Garden of the Gods, [*A unique group of sandstone rock formations near the high mountains.] located only a few miles from the HP plant. A small creek flowed peacefully through the large trailer-home complex. My bedroom window offered a magnificent view of Pikes Peak. This trailer park looked like a pleasant place to spend my summer.

The first evening, however, I heard some commotion nearby. After going to investigate, I saw a police officer struggling with a burly man next to one of the trailers. The officer was trying to handcuff the intoxicated man, who was not cooperating. Confident about my Vic Tanny muscles, I stepped in to help. The two of us managed to subdue the troublemaker. The officer handcuffed him and shoved him into the patrol car. Before leaving, the police officer thanked me for my assistance.

I learned the drunk had wanted to enter the trailer owned by his former girlfriend. When she refused to let him in, he tried to force his way. She had called the police, but the intruder still refused to leave. When the officer attempted to arrest him, he resisted. That was when I came upon the scene. Later, the trailer park’s manager came to see me. To show his appreciation for my help with protecting his tenant, he installed a TV in my unit free of charge.

The oscilloscope division of HP was one of three large electronics companies on the north side of Colorado Springs. To reach the newly built plant, I drove through the unpaved, pothole-riddled Garden of the Gods Road. At the beginning of the road stood a sign: “Rough road for the next 3.1 miles.” The road must have been in poor condition for some time, because a driver with a sense of humor had crossed out the word “miles” and written “years.” I drove my old Chrysler very carefully to work.

Professor Wicks had told me that HP would be a very nice place to work, but I was not prepared for how impressive it was. Compared to the factory where I had worked in Budapest, HP looked like a palace, with clean shining floors, spacious workplaces, sparkling odorless bathrooms, and an attractive cafeteria. Everyone was friendly and helpful. My supervisor let me take time off from work three times a week to take a course at the CU Extension. I decided that HP was the company I wanted to work for after graduation.

|

Three pictures showing parts of the Garden of the Gods. The snow-capped mountain in the background of the right-hand photo |

One day, as I was hurriedly driving to the downtown location of the school, I passed a police car at one of the intersections. The officer immediately turned on his flashing red lights and stopped me for speeding. I was surprised, because I was moving at the speed limit of 35 mph. He pointed out that the speed limit changed to 20 mph only a few blocks back and gave me a ticket. I tried to explain that I had been unaware of the change, but he did not relent.

When my colleagues at work heard what had happened, they told me to make an appeal to the traffic court judge. “Explain to him that you’re only here for a summer job. He may waive the fine,” suggested one. I decided to follow his advice and went to court a few days later.

Once it was my turn, I pleaded “guilty with explanation.” When I delivered my excuse of not being aware of the speed limit change, the judge did not look sympathetic. Just as he was about to fine me, I heard a voice behind me. “Your honor, may I speak on behalf of this man?”

I turned around and recognized the police officer I had helped a few weeks earlier at the trailer park. The judge agreed, and the officer told him about the trailer park incident.

“Well, we don’t want Mr. Besser to have bad memories of our city,” said the judge, as he changed my violation to a warning. “Next time, think carefully before you pass a police car,” he added. I thanked the police officer and left happily without a blemish on my driving record.

The summer of 1965 brought an unusual amount of rain to Colorado. Flash floods gushed down the canyons, and rivers overflowed their beds. Part of the four-lane highway between Denver and Colorado Springs was washed away. The small creek that passed through our trailer park rose to an alarming level, coming close to flooding the area. For the first time in my life, I was a witness to the destructive power of water. It left a lasting impression on me, and I decided never to live in a potential flood zone again.

|

An article taken from a Colorado Springs newspaper |

My last year at CU, 1965-66, looked promising. I had leadership positions in the student government and the honorary societies. My cumulative 3.58 GPA virtually assured graduation with honors. Our soccer team had elected me captain. The U.S. economy was booming, and company interviewers swarmed our campus. I felt confident that I would find a good engineering job after graduation.

Although I was grateful to Canada for allowing me to immigrate in 1956, I planned to settle in the United States after graduation. My student visa would expire once my studies ended, but I could remain working in the United States for an additional 18 months under the “Practical Training Program.” [*This program is still in existence under the name of Optional Practical Training (OPT).] Hewlett Packard, headquartered in California, was my desired destination after graduation. Once employed at HP, the company could request a permanent visa and a Green Card for me from the INS.

Seeing the large number of companies offering campus interviews, I decided to talk with as many firms as possible, beginning in the fall. That way I would have lots of practice before the HP interview, which I planned for the following spring.

After preparing a résumé, I signed up for interviews with 20 companies in the fall and another 20 in the next spring. I selected different industries, ranging from long-established giants such as General Electric, U.S. Steel, IBM, and Standard Oil, to new high-tech companies like Texas Instruments, Varian, and Motorola. In addition, for variety, I added firms like Hallmark Cards, Lever Brothers, and Boeing.

Good news reached me from Hungary. The Communist government had granted a general amnesty to all those who left the country illegally in 1956. I immediately applied for a Canadian passport and planned to visit Budapest the next summer, after graduation. When my passport arrived, the package included a warning. It stated, “Canada will protect its naturalized citizens while they visit foreign countries, except when they are within the borders of their country of origin.” Reading the italicized clause concerned me. Would the Hungarian officials still remember my mischief with the personnel records at our factory in 1956? Could I end up in jail? The note with the passport made it clear that I would be on my own if I were in trouble in Hungary.

One of the Hungarian-American newspapers carried a timely article on this subject. A reporter traveled to Hungary and raised the question to the authorities, “Does the amnesty guarantee safety to every visiting former Hungarian, regardless of what offense they may have committed during the revolution?”

The government official would not give a straight answer. “Not everyone will receive visas to enter Hungary. Those who receive one don’t have to worry,” he said. “They’ll be welcomed on their return—unless of course they do something illegal during their stay.” He had no other comment.

That diplomatic answer sounded like the government might refuse entry visas to some of the revolutionaries rather than arrest them for what they had done. The reporter also added that Hungary needed Western currency. If only half of the 200,000 who had escaped to the West in 1956 returned to visit their country, they would generate significant tourist revenues.

After reading the article, I applied for a Hungarian visa. It took several months, but I finally received it. The Party had either forgiven my “sins” or lost the records. I began planning for a two-week stay. My mother was equally excited to hear about my plan. It had been almost ten years since we had seen each other.

More good news came from my sister. She was expecting their first child the following summer. I promised her I would stop in Montreal for a short visit on my return from Hungary.

My campus job interviews progressed extremely well. The combined Engineering-Business curriculum with its extra course work paid off. Nearly all of the companies that talked with me at CU followed up with invitations to have additional interviews at their facilities.

In most cases, trips to visit a company would require taking two days off from school, but I did not think that would cause any problem. On the first day of a typical interview trip, I would fly to the nearest airport and check into a hotel. On the following day, someone from the company would meet me for breakfast and take me to the plant for the interviews. At the conclusion, they usually provided a little tour of the neighborhood before taking me back to the airport. The company, of course, paid all my expenses.

Perhaps the most interesting experience of these trips occurred during my visit to Texas Instruments (TI) in Dallas. I was somewhat leery of going to the city where President Kennedy had been killed, but after hearing that TI was one of the world leaders of transistor manufacturing, I agreed to visit the company.

At the plant, the personnel representative introduced me to my host for the day—a man whose head was not much above the level of my waist. “Mr. Kitchen is one of our engineering managers,” the administrator told me. “He’ll spend the day with you finding out what part of our operation would be the best fit for you.”

Mr. Kitchen walked me back to his work area. His desk and chair were just the right size for him, but he offered me a regular chair. We sat in the middle of a large office section, separated from others only by low partitions. He explained that very few employees at Texas Instruments had private offices. “The open environment helps to find someone when needed.” With a smile he added, “Unless they are as little as I am.”

At the beginning of our conversation, I was extremely uncomfortable. Is this a setup to see how I behave under unusual circumstances? Is he a real manager or just an actor who is testing me?

As he talked about the company, their products, and the structure of their R&D department, I began to relax. He sounded like a very knowledgeable engineer. He asked many questions regarding my previous experience. I liked him and by lunchtime had begun to consider TI as a possible place to work.

During the afternoon, I spent time with several of his colleagues who worked in different departments. They showed me the various steps of semiconductor manufacturing and testing. At the end of the day, Mr. Kitchen reappeared. “Our director of marketing would also like to talk with you. Would you be able to stay in Dallas overnight?”

I agreed. He told me that we would have dinner at a Texas-style steak house, but first we would stop by his house to pick up his wife. Once we were in his car, I saw that his feet could not reach the foot pedals and that all the controls were mounted on the steering wheel. Inside his house, I felt like Gulliver in Lilliput. With a few exceptions, everything was about two-thirds of the standard size. His charming wife was a couple of inches shorter than he was.

During our ride to the restaurant, they explained the culture of the “Little People,” as they called themselves. Well over 100,000 of them lived in the United States at that time. They belonged to various organizations and led active social lives. Their children sometimes inherit their short stature but can also be of normal size.

After parking the car, we walked into the narrow hallway of the steak house and stopped at a set of Dutch doors. Shortly after, the maitre d' appeared on the other side. “Dinner for one?” he asked, looking at me.

“No, there’re three of us,” I replied.

“Are they still parking the car?”

“No. They’re here.”

“Where?”

“Right here,” I said pointing downward.

The man looked confused for a moment but stepped forward and peeked down over the top of the Dutch doors. Then he saw my two companions.

I will never forget the expression on his face. He stood there for a moment in shock. After he regained his composure, he led us to our table. Mr. Kitchen ordered a huge steak for me. That was only the second time I had tried one, and it was delicious—nothing like the first one I’d had in Montreal.

The following day, my interview continued with TI’s marketing group. Their job descriptions also sounded very interesting. I concluded that I would work in engineering for a couple of years and then transfer to marketing. I added TI to my list of potential employers.

Back in school, halfway through the semester, our landlady suddenly died. By that time, Dick and I had become very fond of her and felt truly saddened by her death. Her son, who inherited the house, decided to sell it. We moved into another apartment about two miles away from the campus, ending the convenience of having short walks to our classes.

Proximity to campus mattered less to me during this time, anyway. Since I had begun pursuing interviews all over the country, I was missing classes regularly. I enjoyed the traveling and seeing how the various companies operated so much that I was willing to let my grades slip. In most courses, the difference between receiving an A or a B depended on handing in all the homework. Therefore, I focused on studying enough to get B’s and skipped the homework.

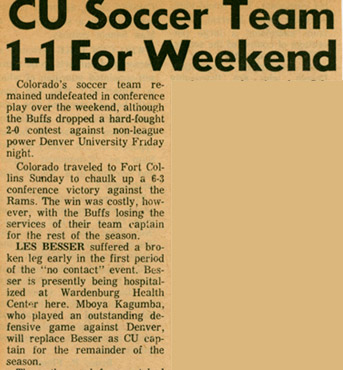

|

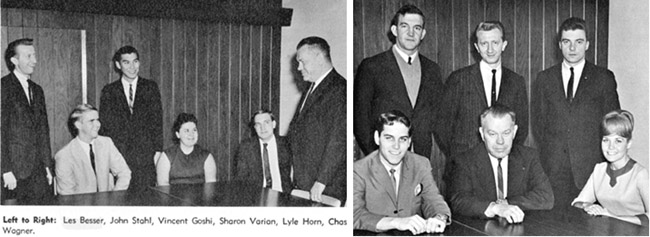

| The memorable CSU game that sidelined me for the rest of the soccer season. That was the last time I played on CU’s team. |

My travels also pulled me away from the daily soccer practices, but I did my best to be there for all games. Our soccer team’s long-standing undefeated record ended when we lost a non-league match to Denver University. Knowing that we had two games scheduled for the weekend, on Friday our coach had spared most of the first-team players for the league game. I was not there to witness our defeat by the DU team, which was heavily reinforced by Norwegian skiers. Two days later, fired up by our loss, we traveled to Fort Collins to play against Colorado State University.

We played well and had a commanding 4-0 lead by the middle of the first half. Then, CSU substituted in several football players. They began to play rough, injuring two of our forwards. The referee lost control over the game and did not throw out the fouling CSU players. In the middle of the second half, during a close battle to control the ball, the CSU center kicked my leg hard behind the shin-guard. I fell down. When I stood up, the leg did not feel right and I signaled for a substitute. After limping to the side, I sat and massaged my aching leg. When we returned to Boulder after winning the game 6-3, I got an X-ray. It showed bad news; I had a fractured fibula.

The next day, the doctors placed a walking cast on my left leg. I used crutches for a few days and then was able to walk without support. The cast stayed on my leg for six weeks. My only consolation was finding out that the CSU player who had kicked me so viciously had received a suspension for the rest of the soccer season.

Although the walking cast slowed me down, I continued with the interview trips. By the end of the first semester, I had garnered 15 job offers but I was still not willing to make a final decision until my visit to HP in the spring. Because I was traveling so much, I earned mostly B’s in the first semester and my grade average dropped somewhat. However, it still looked like I would be able to graduate with honors.

In 1966, under the presidency of Lyndon Johnson, the Vietnam War escalated. Because I was a Canadian citizen on a student visa, the war did not affect me personally. Many of my classmates, however, faced the draft after receiving their degrees. The demand for engineers in the United States increased even more. During the second semester, I continued signing up for additional interviews. I was able to make up the classes I had missed during the trips—except in one course.

The exception was the Semiconductor Material Science course, taught by Professor C. Back when the term started, he had announced an unusual way of deciding when he would give us an unannounced pop quiz. “Statistical probability is very important in our subject,” he began. “At the beginning of each class, I’ll throw a pair of dice on the floor. If the sum of the two comes to seven, [*Seven has the highest probability of being rolled (a one in six chance), while two and twelve have the lowest (each has only one in 36 chance).] I will give you a quiz. A significant part of your grade will be determined by those tests.”

I tried to be funny. “It’s not fair. Those are your dice and you do the throw. Let us do that,” I suggested.

“Fine. That will be your task,” he agreed promptly.

For the next three weeks, my throws never came up to seven. The professor was surprised and began to eye me suspiciously. Then I went away for an interview and the classmate who took over my role threw the unlucky number. The class had a quiz. After I came back, my luck resumed. The professor had me alter the ways I tossed the dice first forward, then backwards against the wall. Still, I never rolled a seven. Finally, he lost his patience and said, “I don’t know how you do it, but you must be cheating.” He took over the task for the rest of the course. After that, the occurrences of pop quizzes followed the expectations of probability. Because I traveled so much, I missed several of those tests. Professor C. did not let me take them later. I was not too concerned. Even if I received a C in that course, it would not hurt me—I thought. I continued traveling.

On one of the trips to the Chicago area, I visited two companies, Motorola and U.S. Steel. I observed an interesting contrast between their management teams. The gray-haired U.S. Steel managers, immaculately dressed in dark business suits, told me about their two-year rotational new employee-training program. Only after the initial 24-month period would they decide where I would work. At Motorola, most of the managers were in their late 20’s or early 30’s. They dressed informally. The company was growing rapidly, and the expansion created advancement opportunities for young people within a few years. Motorola took me to lunch in their bustling noisy cafeteria where the managers mingled with other employees. In contrast, with the U.S. Steel managers, I had eaten at a quiet prestigious club in downtown Chicago. During that meal, I had wondered how long it would take me to reach management ranks. I definitely preferred Motorola’s style of operation.

My last two job interviews took me to Palo Alto, California, to see Varian and Hewlett Packard’s Microwave Division. After receiving a good review from the Colorado Springs group of HP, I assumed that their California interview would be just a formality. It did not turn out that way.

The first man, from HP Personnel, was extremely friendly. He asked about my trip and college life and complimented me on my school achievements. I expected to receive a job offer from him right there. Instead, he turned me over to a second man, T.D., who sat at a small conference table in the middle of an open work area.

T.D. was a short man with a booming voice. After our introduction, he looked at my résumé and began to ask questions. “What do you know about S-parameters?”

“I don’t know what they are,” I replied quietly.

“Oh, you don’t know,” he bellowed. “Do you know how to solve flow-diagrams?”

I lowered myself on the chair and admitted, “No, I don’t.”

He frowned, and in his loud voice, asked two or three more questions related to microwave technology. I had no idea about those either. My chance of working for HP seemed to be vanishing.

“I see you had two semesters of EM field theory. Haven’t you learned anything about high frequencies?” he asked impatiently. People around us began to stare at me.

“I know how FM radios work,” was my hopeful answer.

“OK, tell me about that.”

I grabbed that last chance and explained the difference between AM and FM broadcasts. Drawing on my technical high school experience, I drew a block diagram of an FM radio. By the time I began to talk about the radio’s circuitry, he was satisfied. “Although we need to teach you about microwaves, I feel that you’ll be able to pick it up quickly,” he told me. After shaking my hand, he turned me over to the third person of his team.

During the next half hour, his colleague took me for a plant tour. Then he had me talk with three more people, one in the research and development group, one in the production area, and finally one in marketing. The last person took me back to Personnel where I learned that a job offer would be mailed to me the next day. My new dream would come true—I would live in California and work for HP!

Back in Boulder, I received HP’s letter a few days later. I would be a project engineer at a monthly salary of $850. The company promised to pay all my relocation expenses as well as local hotel accommodations until I found a suitable living arrangement. As we agreed, I would report to work late June, after returning from my trip to Hungary.

In today’s economy, it sounds incredible, but counting HP’s job offer, I had received over 30 offers from companies all over the country. I wrote and sent a polite reply to every one, explaining that the combination of HP’s work environment and California living was something I could not turn down.

I was in heaven. Only a few weeks remained until graduation. After my long-anticipated trip to Hungary, an exciting job would be waiting for me. Actually, I was not even going to attend the graduation ceremonies. In my haste to see my mother again, I planned to leave for Hungary the day after my last final.

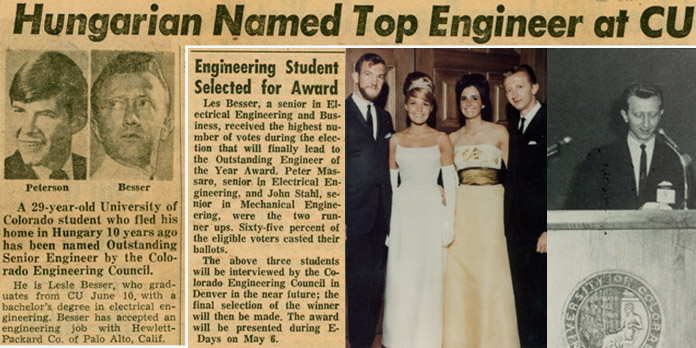

Near the end of the school year, I received several honors. In the Outstanding Engineer of the Year competition, the engineering students voted me to become one of the three finalists. Shortly after, the Colorado Engineering Council selected me as the winner. I was also named one of the 20 Pacesetters of the University’s 17,000 students, based on “Leadership, character, service to the University, and academic excellence.” That came with the added distinction of being included in Who’s Who Among Students in American Universities and Colleges. At a fancy ceremony, the mayor of Boulder handed each of the Pacesetters the award and a key to the city.

Being active in student government provided several benefits. Interviewing the candidates for queen of the Engineers Ball was one of them. In addition to the interview, the five committee members could take the top five contestants to the ball. My date, the daughter of a Denver socialite, was the first runner-up. I proudly danced with her at the ball, held at a country club. When the ball ended, I drove her back to the sorority house where she lived. About three blocks away from the house, she wanted me to stop the car. “Let’s walk from here,” she said. I was surprised because it was raining outside. After we parted, the reality hit me—she did not want her sorority sisters to see her stepping out of my 20-year-old car!

|

Left: Two articles from the Boulder newspapers. |

Just when I thought that I was on the top of the world, the unexpected happened. Two weeks before the final exams, the secretary of the EE Department office called me.

“Professor C. has turned in the expected grades for the semester, [*The department head wanted advance notice of the students who were to graduate that semester.] and he plans to flunk you,” she told me.

Her news struck me like a lightning bolt. I had already accepted a job with HP and paid for my flight to Hungary. If I failed that required course, I would not graduate. What can I do?

My pride did not allow me to go begging to the professor. It would probably not have helped anyway, because he could easily point out all the tests I had missed. Instead, dropping everything else, I began to study hard for the final exam of that course. My guardian angel probably came to my rescue again, because I received one of the top scores on the final. Professor C changed my grade to a D. It was nothing to brag about, but I passed his course! However, I missed graduating with honors by one tenth of a point.

Shortly before I left for Hungary, a Denver Post reporter interviewed me and wrote a nice article about my background. The photo that appeared in the article showed me with my mentor professor, Dr. Wicks, in the lab.

|

Professor Wicks, my CU mentor, had been like a father to me. |

Computer dating on campus began about a month before I graduated. The student newspaper published a lengthy personality questionnaire and, for two dollars, offered to match a person with three highly compatible dates. With my background in engineering, I trusted computers and sent in the completed form with the money. During the busy weeks of May, I completely forgot about the service. It was only when my forwarded mail reached me in California a few weeks later that I learned what I had missed. The dating program had sent me the names of three “like-minded” girls. After looking at their photos in the college yearbook, I wished that I could have waited another week before taking my trip.

During the early years of my childhood, while Pista’s family was raising me, my mother could only visit me sporadically. She always took me to play in Budapest’s Városliget (City Park) where she would buy a large pretzel for us to share. On one of those occasions, I promised her, “When I grow up and become rich, we’ll come here in our car and each of us will have a full pretzel.” Remembering that promise, I wanted to have a car during my visit, but renting one in Eastern Europe would not be easy. I decided to fly to Vienna, pick up a rental car at the airport, and drive to Hungary. Arriving in a Western car would also impress everyone who knew me.

Although the Denver-Vienna flight included two stops during the overnight trip, I did not feel tired. After picking up a Ford Taurus from AVIS, I sped toward the Hungarian border 65 kilometers (40 miles) away.

When I reached the Austrian border, the guard let me pass without even stopping. On the Hungarian side, several cars ahead of me waited for clearance. I saw border guards armed with submachine guns walking around those cars.

Suddenly I lost my courage and considered turning around. I remembered the recurring dreams I had experienced after escaping from Hungary. The basic theme was always the same: I would illegally sneak back to Hungary, only to find myself in the midst of another revolution. In my dreams, I always asked myself how I could have been so foolish as to return.

I tried to calm my nerves. There will not be another revolution. The Hungarians learned the hard way that they could not defeat the Red Army. This time is different. I am going back with a legal visa. I continued to inch forward until the Hungarian guard halted me.

“Paß bitte,” (Passport please) he said sternly in German, seeing my car’s Austrian license plate. I handed my passport and visa to him while speaking Hungarian. He became friendlier and looked through my documents.

“I see you are one of the fifty-sixers, [*One of the questions in the Hungarian visa stated, “If you have ever been a citizen of Hungary, when did you leave the country?” My answer, “November 1956,” made it obvious that I was one of the illegal escapees.] was his next comment. “What brings you back this time?”

“I haven’t seen my mother for ten years. I also want to eat some real Hungarian food.”

He laughed and asked if I was bringing any gifts with me. Hearing that I had only small items, he took the documents into the guardhouse. A few minutes later, he reappeared and handed back my papers. “Drive carefully and remember to register at the district police station within 48 hours,” were his parting comments.[*Residence registration was a legal requirement for all Hungarians and foreign visitors.] He lifted the border gate and waved me through. I sighed with relief and quickly drove away.

A four-lane highway on the Hungarian side was partially completed. Although I was very hungry and some of the roadside restaurants emitted tempting aromas, I was not about to stop. In a few hours, I reached the outskirts of Budapest. In my excitement, I missed a detour sign and drove into a section of the road that was under construction. A police officer stopped me.

I made the mistake of talking to him in Hungarian. If he had thought that I was a foreigner, most likely he would have let me go. Instead, he told me that I had to pay a fine of 100 forint. I did not have any Hungarian money and asked if I could pay with U.S. dollars. “It’s illegal for Hungarians to handle Western currency,” he informed me. “You must first exchange your money and pay the fine in forints.” He gave me the address of his district police station and specifically instructed me to hand the money to a “Sergeant Balco.” I promised to comply the following day.

A little shaken by the incident, I drove carefully to the apartment building where my mother lived. Traffic was relatively light, mostly busses and streetcars. The few passenger cars on the streets were small and noisy. The mufflers of the Soviet-made Ladas and East German Trabants spewed stinky, smoky fumes. Compared to American store windows, the ones in Budapest looked bare. However, the sidewalks were clean, and I did not see any beggars.

Finally, I reached the place where I had lived for 14 years. A camouflage-painted van, with a communication antenna mounted on its top, sat parked in front of the apartment building. Seeing the military vehicle in the civilian neighborhood alarmed me. Is someone waiting here to spy on me?

I stopped behind the vehicle and observed it for some time. Then, a soldier came out of the building, waved to someone looking out through an open window, climbed into the van, and drove away. Relieved, I took my suitcases and walked up to our apartment. Mother heard my knocking and opened the door with tears running down her cheeks. We hugged each other for a long while. Then she pulled me into the kitchen, where I could smell one of my favorite meals—stuffed cabbage. The table was already set for two.

I was shocked to see how much her appearance had changed. She had not mailed me any pictures, so I still carried a mental image of her from 1956. She appeared to have aged 20 years during my ten-year absence.

Other than her looks, everything else seemed the same in the apartment, except that now she had a small television in the living room. Before I could open my bags, she had me sit at the table and served me a huge portion of the cabbage. She also opened a large bottle of beer and poured for both of us. “Eat, my son,” she encouraged me. There was no need to tell me twice.

Her appearance might have changed. Her food, however, tasted just as good as before. I stuffed myself and listened to her quick summary of the past years. Life had not been easy for her. Hearing the hard times she had faced, I was overwhelmed by guilt for having left her behind. She probably read my mind, because she changed the subject and told me how proud she was to have a son who was a college graduate. That had been beyond her wildest dreams. Hearing that from her made me feel somewhat better.

We chatted the rest of the evening while she kept giving me slices of my favorite dessert, dobos-torta (a multilayer cake with hard caramel topping.) Eventually, I could not keep my eyes open. We said good night to each other and prepared to retire. The two students who had been renting the spaces in the living room were away for summer vacations, so I could sleep on my old familiar sofa.

The next morning I went to exchange money and register my stay at the local police station. When the officer in charge heard that I had been directed to pay the fine to a specific sergeant at another station on the Buda side, he became curious and made a phone call to inquire. I was in the room during the lengthy call and watched him shake his head in disbelief. When he finished, he turned to me. “There was a misunderstanding,” he said while tearing up my citation. “You don’t need to pay anything.” I suspected some illegal activity and concluded that Montreal was not the only city with crooked police.

Mother reminded me that Cousin Pista was eager to see me. Since their marriage five years earlier, the young couple had shared a three-bedroom apartment with the wife’s parents and her married brother’s family. Pista and his wife, Kuki, had two children, ages two and three. Altogether, three couples and four children squeezed into an apartment that had one bathroom and one kitchen. The grandparents had been living in the large apartment since the late 1930s. When their two children married, like many others in war-torn Budapest, they moved in with the parents and raised their babies there.

In the evening, carrying the large Colorado University yearbook and some small presents, I went to see them. After an emotional reunion, Pista introduced his “American cousin” to the family. Then he said, “Tell us about America.”

“Wait!” interrupted his wife. She jumped up, closed the windows facing the street, and pulled down the shades. “There is a military installation across the street,” she explained. “They may have listening devices.” Suddenly, I realized that I was behind the Iron Curtain, where overhearing a conversation contrary to the Party’s philosophy could lead to trouble. Although the thick walls assured privacy, we kept our voices low.

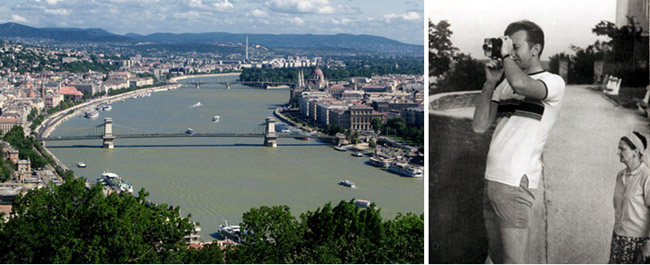

|

Left: Picture of Budapest, taken from Mount Gellért. Five bridges over the Danube link the two sides, Buda and Pest. |

Although I spent most of my time in Hungary with Mother, I was able to meet with some of my former track teammates and coaches who had not left the country after the revolution.

We enjoyed recalling the experiences we had had during our running days. Most of the ones I met wished they had also escaped in 1956.

My mother told me that a few weeks earlier she had received a letter from an elderly aunt who lived in a small village. “When I had you out-of-wedlock, most of my family shunned me. Now, Aunt Manci wants me to visit her,” she said. “Could we go there in your car?”

I had not met her aunt, and the idea of visiting a small village was not particularly appealing. However, to make Mother happy, I agreed. Because only a relatively small number of people had telephones, we had no easy way to announce our visit. We just took off for the journey the next Sunday with the hope that the aunt would be at home to see us.

Aunt Manci welcomed us with open arms. She was very thin and wore the customary black Sunday outfit of country women. Her face was wrinkled and her happy smile revealed many missing teeth. After seating us at an outdoor table, she served various meats and bread and urged us to eat. I was not bashful and helped myself to the delicious sausages, bacon, and home-baked bread.

The appearance of a foreign car in the village was unusual. News of an American visitor spread rapidly. Within a short time, curious neighbors surrounded the Ford. Their children were bolder and spilled into the backyard. They sat politely and watched every move we made. I felt like I was on a stage.

The aunt told us that she had always loved my mother, but her husband had forbidden contact with the “outcast of the family.” After the husband passed away, she located Mother and wanted to make up for the missing time. “I’m sick and probably don’t have too long to live,” she confided to us, coughing frequently. “I had to see my favorite niece before I go.”

She was sweet, and by the time we left, I felt very affectionate toward her. It was like meeting the grandmother I had never seen. She wanted us to stay overnight, but I only had two more days left in my visit. We wished her all the best and drove back to Budapest.

The last day of my stay came too quickly. To extend our time together as long as possible, Mother suggested that we drive together in my car to the last permitted city near the border. [*Only the local residents and visitors with special permits were allowed to be within the 10-km-wide Western border zone.] From there she would return to Budapest by train while I continued to Vienna.

We were quiet at the beginning of the ride, knowing that we would soon be separated once more. When we finally started talking, I promised to visit again. I told her I would look into the possibility of her coming to California. I asked if she would consider living there permanently. “If I were your age, yes,” she replied. “But at my age, starting life again would be too difficult. As long as I can see you and Éva at times, I’ll be happy.”

At the city of Győr, I walked her to the train station. We said tearful good-byes and parted. With a heavy heart, I waited until the train pulled out and then returned to the car. Within a half hour, I arrived at the heavily fortified border area.

Leaving Hungary was not as easy as entering it had been. Heavy guardrails protected the road. Border patrol officers toting submachine guns swarmed the area. When I reached the first checkpoint, a guard asked for my passport and visa and took the documents into the guard station. A few minutes later, he returned with two other guards. “Where is your mother?” he asked.

“She is on the train back to Budapest.” I wondered if they had been tracking me.

“Leave your keys in the car and step into the station,” the guard commanded in an official tone.

I hesitated for a moment. Were my recurring dreams more than nightmares—possibly premonitions? How can I escape now?

I realized I had no choice but to comply. Crashing through the two sets of gates seemed improbable. Even if I could pass the first one, the guards on the other side could easily cut me down. I remembered that shooting someone during an escape attempt led to promotions for the shooters. They would not hesitate to open fire. I resigned myself to my fate and stepped out of the car. The guard led me into a small room in the station and told me to wait.